[Page 1]

An Exposition

of

GENESIS

by

R. S. Candlish

SOVEREIGN GRACE

PUBLISHERS

1972

[Page 2]

In order

to make this book more universally useful, not only for

the highly educated or

long-experienced person, but for the young person who

has but little experience

with Elizabethan English, this work has the advantage of

the KING JAMES

II VERSION in all its lead

verses. In

this way all will be able to

absorb immediately what God has actually said, and thus

to quickly perceive the

value of the excellent insights of Mr. Candlish, the

author.

Since Mr. Candlish may not be known to all readers as a

Presbyterian, those who are Baptists, and other

immersionists, among employees

of the publisher, desire to disclaim those remarks that

imply there is a

connective succession between circumcision and baptism,

and other Paedo-baptist

views expressed herein by the author.

Needless to say, all of the staff concurs in

believing this to be

excellent exposition, fitted to make one wise and more

useful to God.

-------

[Page 3]

PREFACE

The

appendix at the end of the second volume of this

publication contains a brief

statement of some general views regarding the Book of

Genesis, which have impressed

themselves on my mind in the course of study.

Having carefully revised the entire work, I have agreed to an

alteration of the title.

I wish it to be

understood, however, that I still offer these papers

merely as “Contributions

towards the exposition of the Book of Genesis;” - not by any means entitled to the character of a full and

exhaustive exposition.

The change of

title is simply meant to indicate that I offer to the

public a commentary upon

the whole book.

-------

[Page 4 blank:

Page 5]

TABLE

OF

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

CREATION VIEWED AS

MATTER OF FAITH

Page 9

CHAPTER 2

THE CREATION OF THE WORLD

AND MAN VIEWED ON ITS HEAVENLY SIDE

Page 18

CHAPTER 3

THE CREATION OF MAN VIEWED AS ON THE SIDE OF EARTH;

AND HIS EARTHLY ORIGIN AND RELATIONS

Page 28

CHAPTER 4

DEVOTIONAL AND PROPHETIC

VIEW OF THE CREATION,

BEING AN APPENDIX TO THE

TWO PRECEDING PAPERS

Page 35

CHAPTER 5

THE FIRST TEMPTATION -

ITS SUBTLETY AS IMPEACHING

THE GOODNESS, JUSTICE,

AND HOLINESS OF GOD

Page 44

CHAPTER 6

THE FRUIT OF THE FIRST SIN - THE REMEDIAL SENTENCE

Page 51

CHAPTER 7

THE FIRST FORM OF THE NEW DISPENSATION -THE

CONTEST BEGUN BETWEEN GRACE AND NATURE

Page 60

CHAPTER 8

THE APOSTATE SEED - THE GODLY SEED –

THE UNIVERSAL CORRUPTION Page 73

CHAPTER 9

THE END OF

THE OLD WORLD BY WATER –

THE COMMENCEMENT

OF THE NEW

WORLD RESERVED UNTO FIRE …Page

84

CHAPTE R 10

THE

CONSTITUTION OF THE NEW WORLD, IN

ITS THREE DEPARTMENTS

OF NATURE,

- 1. THE LAW

OF NATURE …Page 92

CHAPTER 11

THE

CONSTITUTION OF THE NEW WORLD, IN

ITS THREE DEPARTMENTS

OF NATURE,

- 2.THE

SCHEME OF

CHAPTER 12

THE

CONSTITUTION OF THE NEW WORLD, IN

ITS THREE DEPARTMENTS

OF NATURE,

- 3. THE

ELECTION OF GRACE

Page 101

CHAPTER 13

THE EARTH

GIVEN TO THE CHILDREN OF

MEN,

AND OCCUPIED

BY THEM …Page 108

CHAPTER 14

THE CALL OF

ABRAM - HIS JUSTIFICATION

– THE POWER OF HIS FAITH,

AND ITS

INFIRMITY Page 116

CHAPTER 15

THE

INHERITANCE OF THE LAND PROMISED

TO ABRAM Page

124

[Page 6]

CHAPTER 16

VICTORY OVER

THE INVADERS OF THE LAND

-

INTERVIEW

WITH MELCHIZEDEK

Page 133

CHAPTER 17

JUSTIFICATION

BY FAITH INSIGHT INTO

THINGS TO COME

Page

146

CHAPTER 18

THE TRIAL OF

FAITH - ITS

INFIRMITY Page

160

CHAPTER 19

THE REVIVAL

OF FAITH - THE REPETITION

OF THE CALL

Page

166

CHAPTER 20

THE RENEWAL

OF THE COVENANT

Page 170

CHAPTER 21

THE SEAL OF

THE COVENANT –

THE SACRAMENT

OF CIRCUMCISION

Page 175

CHAPTER 22

ABRAHAM THE

FRIEND OF GOD

Page 183

CHAPTER 23

THE GODLY

SAVED, YET SO AS BY FIRE;

THE WICKED

UTTERLY DESTROYED

Page 196

CHAPTER 24

THE

IMPRESSION OF THE SCENE WHEN ALL

IS OVER Page

206

CHAPTER 25

CARNAL POLICY

DEFEATED - EVIL

OVERRULED FOR GOOD

Page 209

CHAPTER 26

THE

SEPARATION OF THE SEED BORN AFTER

THE FLESH

FROM THE SEED THAT IS BY PROMISE

Page 215

CHAPTER 27

ALLEGORY OF

ISHMAEL AND ISAAC - THE

TWO COVENANTS

Page

220

CHAPTER 28

THE TRIAL, TRIUMPH, AND REWARD OF ABRAHAM’S FAITH

Page 225

CHAPTER 29

TIDINGS FROM HOME - THEIR CONNECTION WITH SARAH’S

DEATH AND ISAAC’S MARRIAGE

Page 236

CHAPTER 30

THE DEATH AND BURIAL OF A PRINCESS

Page 239

CHAPTER 31

A MARRIAGE CONTRACTED IN THE LORD

Page 247

CHAPTER 32

THE DEATH OF ABRAHAM

Page 256

CHAPTER 33

THE LIFE AND CHARACTER OF ABRAHAM

Page 259

CHAPTER 34

THE FAMILY OF ISAAC - THE ORACLE RESPECTING JACOB AND

ESAU

Page 267

[Page 7]

CHAPTER 35

PARENTAL FAVORITISM AND FRATERNAL FEUD

Page 270

CHAPTER 36

THE

ADVENTURES IN HIS PILGRIMAGE

Page 276

CHAPTER 37

THE TRANSMISSION OF THE BIRTHRIGHT-BLESSING

Page 279

CHAPTER 38

THE BEGINNING OF JACOB’S PILGRIMAGE - THE VISION

Page 288

CHAPTER 39

THE BEGINNING OF JACOB’S PILGRIMAGE - THE VOW

Page 293

CHAPTER 40

JACOB’S SOJOURN IN

CHAPTER 41

JACOB'S SOJOURN IN

CHAPTER 42

JACOB’S SOJOURN IN

CHAPTER 43

JACOB’S SOJOURN IN

CHAPTER 44

THE PARTING OF LABAN AND JACOB

Page 317

CHAPTER 45

THE TWO ARMIES - THE FEAR OF MAN -

THE FAITH WHICH PREVAILS WITH GOD

Page 323

CHAPTER 46

JACOB’S TRAIL ANALOGOUS TO JOB’S

Page 330

CHAPTER 47

THE MEETING OF JACOB AND ESAU -

BROTHERLY RECONCILIATION Page 336

CHAPTER 48

PERSONAL DECLENSION –

FAMILY SIN AND SHAME Page 341

CHAPTER 49

PERSONAL AND FAMILY

REVIVAL - MINGLED GRACE AND CHASTISEMENT

- AN ERA IN THE

PATRIARCHAL DISPENSATION

Page 347

CHAPTER 50

A NEW ERA - THE BEGINNING OF A NEW PATRIARCHATE

Page 353

CHAPTER 51

THE

CHAPTER 52

SINFUL ANCESTRY OF “THE HOLY SEED” -

GRIEF IN CANAAN - HOPE IN

CHAPTER 53

HUMILIATION AND TEMPTATION YET WITHOUT SIN

Page 367

CHAPTER 54

THE SUFFERING SAVIOR - THE SAVED AND LOST

Page 374

CHAPTER 55

THE END OF HUMILIATION AND BEGINNING OF EXALTATION

Page 381

[Page

8]

CHAPTER 56

EXALTATION - HEADSHIP OVER ALL - FOR THE CHURCH

Page 386

CHAPTER 57

CONVICTION OF SIN - YOUR SIN SHALL FIND YOU OUT

Page 391

CHAPTER 58

THE TRIAL AND TRIUMPH OF FAITH Page 400

CHAPTER 59

THE DISCOVERY - MAN’S EXTREMITY GOD’S

CHAPTER 60

A TRUE BROTHER - A GENEROUS KING - A GLAD FATHER

Page 415

CHAPTER 61

FAITH QUITTING CANAAN FOR

CHAPTER 62

TO BE KEPT THERE TILL THE TIME COMES

Page 428

CHAPTER 63

JOSEPH’S EGYPTIAN POLICY –

CHAPTER 64

THE DYING SAINT’S CARE FOR THE BODY AS WELL AS THE SOUL

Page 438

CHAPTER 65

THE BLESSING ON JOSEPH’S CHILDREN -

JACOB’S DYING FAITH Page 441

CHAPTER 66

JACOB’S DYING PROPHECY -

CHAPTER 67

WAITING FOR THE SALVATION OF THE LORD -

SEEING THE SALVATION OF THE LORD

Page 453

CHAPTER 68

CLOSE OF JACOB'S DYING PROPHECY -

THE BLESSING ON JOSEPH Page 462

CHAPTER 69

THE DEATH OF JACOB HIS CHARACTER AND HISTORY

Page 465

CHAPTER 70

THE BURIAL OF JACOB THE LAST SCENE IN

CHAPTER 71

JOSEPH AND HIS BRETHREN

–

THE FULL ASSURANCE OF

RECONCILIATION Page 478

CHAPTER 72

FAITH AND HOPE IN DEATH –

LOOKING FROM

APPENDIX

OBSERVATIONS ON THE STRUCTURE OF THE BOOK

OF GENESIS AS A WHOLE Page 490

-------

[Page 9]

CHAPTER 1

CREATION VIEWED

AS MATTER OF FAITH

By faith we understand that the worlds were framed

by the word of God, that the things which are seen were not made of

things

which appear. - Hebrews

11: 3.

The view

taken in this Lecture I hold to be important, not only

in its practical and

spiritual bearings, on which I chiefly dwell, but also

in relation to some of the

scientific questions which have been supposed to be here

involved. It

lifts, as I think, the divine record out

of and above these human entanglements, and presents it,

apart from all

discoveries of successive ages, in the broad and general

aspect which it was

designed from the first and all along to wear, as

unfolding the Creator’s mind

in the orderly subordination of the several parts of His

creation to one

another, with special reference to His intended dealings

with the race of man.

On this account I ask attention to what

otherwise might appear to some to be an irrelevant

metaphysical conceit.

It is proposed, then, to inquire what is implied in our really

believing, as a matter of revelation, the fact of the

creation. This

may seem a very needless inquiry, in

reference to a fact so easily understood.

“In the beginning God created the

heaven and the earth.”

“The worlds were framed by the

word of God.”

Can any thing be easier than to comprehend and

believe this great truth

thus clearly revealed?

Who can be at a

loss to know what is meant by believing it?

It is remarkable, however, that in speaking of

that faith whose power he

celebrates as the most influential of all our principles

of action, the apostle

gives, as his first instance of it, our belief of this

fact of the

creation. “Through faith,” - that

particular energetic faith,

which so vividly realizes its absent object, unseen and

remote, as to invest it

with all the force of a present and sensible impression,

- through this precise

faith, “which is the substance of things

hoped for, the

evidence of things not seen,” “we

understand that the worlds were framed by the word of

God;

so that things which are seen

were not made of things

which do appear.”

Now, this faith is peculiar in several respects, and its

peculiarity is as much to be observed in the belief of

the fact of creation, as

in the belief of the fact of redemption, - including, as

such belief does, a

reliance on the promises connect with that fact and

ratified and sealed by it,

springing out of a reliance on the person promising. It is

especially peculiar in respect of its

source, or of the evidence on which it rests.

The truths which it receives, it receives on the

evidence of testimony,

as truths revealed, declared, and attested, by the

infallible word of the

living God.

This is a point of great importance, as it affects both the

kind of assent which we give to these truths, and the

kind and degree of

influence which they exert over us.

There is the widest possible difference between

our believing certain

truths as the result of reasoning or discovery, and our

believing them on the

direct assertion of a credible witness whom we see and

hear, - especially if

the witness be the very individual to whom the truths

relate, and indeed

himself their author.

The truths

themselves may be [Page

10]

identically the same; but how

essentially different is the state of the mind in

accepting them; and how

different the impression made by them on the mind when

accepted.

1.

The difference may be illustrated by

a simple and familiar example.

In the

deeply interesting and beautiful work of Paley on

Natural Theology - for so it

may still be characterized, in spite of lapse of time

and change of taste - the

author, in stating the argument for the being of a God,

derived from the proofs

of intelligence and design in nature, makes admirable

use of an imaginary case

respecting a watch.

He supposes that,

being previously unacquainted with such a work of art,

you stumble upon it for

the first time, as if by accident, in a desert.

You proceed to exercise your powers of judgment

and inference in regard

to it. You

hold it in your hand, and

after exhausting your first emotions of wonder and

admiration, you begin to

examine its structure, to raise questions in your own

mind, and to form

conjectures. How

did it come there, and

how were its parts so curiously put together?

You at once conclude that it did not grow there,

and that it could not

be fashioned by chance.

You are not

satisfied to be told that it has lain there for a long

period, - from time

immemorial, - forever; that it has always been going on

as it is going on now;

that there is nothing really surprising in its movements

and its mechanism;

that it is just its nature to be what it is, and to do

what it does. You

utterly reject all such explanations as

frivolous and absurd.

You feel assured

that the watch had a maker; and your busy and

inquisitive spirit immediately

sets itself restlessly to work, to form some conception

as to what sort of

person the maker of it must have been.

You gather much of his character from the obvious

character of his

handiwork; you search in that handiwork for traces of

his mind and his heart;

you speculate concerning his plans and purposes; your

fancy represents him to

your eye; you think you understand all about him; you

find the exercise of

reasoning and discovery delightful, and you rejoice in

the new views which it

unfolds.

But now suppose that, while you are thus engaged, with the

watch in your hand and your whole soul wrapt in

meditative contemplation on the

subject of its formation, a living person suddenly

appears before you, and at

once abruptly announces himself, and says, It was I who

made this watch - it

was I who put it there.

Is not your

position instantly and completely changed?

At first, perhaps, you are almost vexed and

disappointed that the thread

of your musing thoughts should be thus broken, and your

airy speculations

interrupted, and you should be told all at once on the

instant, what you would

have liked to find out for yourself, - that the riddle

should be so summarily

solved, and a plain tale substituted for many curious

guesses. But

you are soon reconciled to the change,

and better pleased to have it so.

The

actual presence of the individual gives a new interest -

the interest of a more

vivid and intense reality - to the whole subject of your

previous

thoughts. Nor

does this new impression

depend merely upon the greater amount of information

communicated; for the

individual now before you may explicitly tell you no

more than, in his absence,

the watch itself had virtually told you already.

Neither does it arise altogether from the

greater certainty and [Page

11]

assurance of the revelation which he

makes to you; for in truth your own inferences, in so

plain an instance of

design, may be as infallible as any testimony could be. But there is

something in the direct and

immediate communication of the real person, speaking to

you face to face, and

with his living voice, which affects you very

differently from a process of

reasoning, however clear and unquestionable its results

may be.

Your position, in fact, is now precisely reversed.

Instead of questioning the watch concerning

its maker, you now question the maker concerning his

watch. You

hear, not what the mechanism has to say

of the mechanic, but what the mechanic has to say of the

mechanism. You

receive, perhaps, the same truths as

before. They

come to you, - not

circuitously and at second hand, but straight from the

very being most deeply

concerned in them.

They come home to you

without any of that dim and vague impersonality - that

abstract and ideal

remoteness - which usually characterizes the conclusions

of long argument and

reasoning. They

are now invested with

that sense of reality, and those sensations and

sentiments of personal concern,

which the known face and voice of a living man inspire.

2.

Now, let us apply these remarks to

the matter in hand.

We are all of us

familiar with this idea, that in contemplating the works

of creation, we should

ascend from nature to nature’s God.

Everywhere we discern undoubted proofs of the

unbounded wisdom, power,

and goodness of the great Author of all things.

Everywhere we meet with traces

of just and benevolent design, which should suggest to

us the thought of the

Almighty Creator, and of His righteousness, truth, and

love. It is

most pleasing and useful to cultivate

such a habit as this; much of natural religion depends

upon it, and holy

Scripture fully recognizes its propriety.

“The

heavens

declare the glory of God: the firmament showeth his handiwork.”

“All thy works praise thee,

Lord God Almighty.” “Lift up

your eyes on high, and

behold - Who hath

created these things?” “0

Lord, how manifold are

thy

works! in wisdom hast

thou made them all:

the earth is full of thy riches.”

It is apparent, however, even in these and similar passages,

that created things are mentioned, not as arguments, but

rather as

illustrations; not as suggesting the idea of God, the

Creator, but as unfolding

and expanding that idea, otherwise obtained.

And this is still more manifest in that passage of the Epistle

to the Romans which

particularly appeals to the fact of creation as evidence

of the Creator’s

glory, - evidence sufficient to condemn the ungodly: “For

the

invisible things of him from the creation of the world

are clearly seen,

being understood by the things

that are made, even

his eternal power and Godhead; so

that they are without excuse: because that, when they knew God, they

glorified

him not as God, neither

were thankful;

but became vain in their

imaginations, and

their foolish heart was darkened” (1:

20, 21). Here it is

expressly

said, that from the things that are made might be

understood the invisible

things of God, even his eternal power and Godhead; so

that atheists, idolaters,

and worshipers of the creature, are without excuse. But why are

they without excuse? Not because

they failed to discover God, in this way, from His

works, but because, when

they knew God otherwise, [Page

12]

they did not glorify Him, as these

very works might have continually taught them to do: -

not because they did not

in this way acquire, but because they did not like in

this way to retain, the

knowledge of God.

For the fact of the creation is regarded in the Bible as a

fact revealed; and, as such, it is commended to our

faith. Thus

the scriptural method on this subject is

exactly the reverse of what is called the natural. It is not to

ascend from nature up to

nature’s God, but to descend, if we may so speak, from

God to God’s nature, or

His works of nature; not to hear the creation speaking

of the Creator, but to

hear the Creator speaking of the creation.

We have not in the Bible an examination and

enumeration of the wonders

to be observed among the works of nature, and an

argument founded upon these

that there must be a God, and that He must be of a

certain character, and must

have had certain views in making what He has made. God Himself

appears, and tells us

authoritatively who He is, and what He has done, and why

He did it.

Thus “through faith we understand

that the worlds were made by the word of God;

so that things which are seen were not made of things which do appear.” We understand and

believe this, not as a deduction of reasoning, but as a

matter of fact,

declared and revealed to us.

For this is

that act of the mind which, in a religious sense, is

called faith. It

involves in its very nature an exercise of

trust or confidence in a living person, - of

acquiescence in his word, - of

reliance on his truth, on himself.

It

implies the committing of ourselves to him, - the

casting of ourselves on him,

- as faithful in what he tells, and in what he promises. We believe on

his testimony. We

believe what he says, and because he says

it. In thus

simply receiving a fact

declared by another, and that other fully credible and

trustworthy, the mind is

in a very different attitude and posture from that which

it assumes when it

reasons out the fact, as it were, by its own resources. There is far

more of dependence and

submission in the one case than in the other, - a more

cordial and implicit

recognition of a Being higher than we are, - a more

unreserved surrender of

ourselves. The

one, in truth, is the act

of a man, the other of a child.

Now, in

the

[Page 13]

But now, God speaks, and I am dumb.

He opens His mouth, and I hold my peace.

I bid my busy, speculative soul be quiet. I am still,

and know that it is God.

I now at once recognize a real and living

Person, beyond and above myself.

I take

my station humbly, submissively at His feet.

I learn of Him.

And what He tells

me now, in the way of direct personal communication from

Himself to me, has a

weight and vivid reality infinitely surpassing all that

any mere deductions

from the closest reasoning could ever have.

Now in very truth my “faith” does become “the substance of things hoped for, the

evidence of things not seen.”

Now at last I am brought into real personal

contact with the Invisible

One. And He

speaks as one having

authority. He

whom now I personally know

and see tells me of the things which He has made; and so

tells me of them, that

now they start forth before my eyes in a new light. The idea of

their being not only His

workmanship, but of His explaining them to me as His

workmanship, assumes a

distinctness - a prominence and power - which cannot

fail to exercise a strong

influence and exert a sovereign command over me, as a

communication directly

from Him to me.

Such is that faith respecting the creation which alone can be

of a really influential character.

Thus

only can we truly and personally know God as the

Creator.

3.

But it may be asked, Are we, then,

not to use our reason on this subject at all?

That cannot be; for the apostle himself enjoins

us, however in

respect of meekness we are to be like

children, still in understanding to be men.

Certainly we do well to search out and collect

together all those

features in creation which reflect the glory of the

Creator. Nay,

we may begin in this way to know

God. It is

true, indeed, that God has

never, in point of fact, left Himself to be thus

discovered. He

has always revealed Himself, as He did at

first, not circuitously by His works, but summarily and

directly by His

word. We

may suppose, however, that you

are suffered to grope your way through creation to the

Creator. In

that case you proceed, in the manner

already described, to deduce or infer from the manifold

plain proofs of design

in nature, the idea of an intelligent author, and to

draw conclusions from what

you see of his works, respecting his character,

purposes, and plans. Still,

even in this method of discovering God, if your faith is

to be of an

influential kind at all, you must proceed, when you have

made the discovery,

exactly to reverse the process by which you made it. Having arrived

at the conception of a Creator,

you must now go back again to the creation, taking the

Creator Himself along

with you, as one with whom you have become personally

acquainted, and hearing

what He has to say concerning His own works.

He may say no more than what you had previously

discovered; still what

He does say, you now receive, not as discovered by you,

but as said by

Him. You

leave the post of discovery and

the chair of reasoning, and take the lowly stool of the

disciple. And

then and not before, even on the

principles of natural religion, do you fully understand

what is the real import

and the momentous bearing of the fact, - that a Being,

infinitely wise and

powerful, and having evidently a certain character, as

holy, just, and good, -

that such a Being made you, - and that He is Himself

telling you that [Page 14] He made you, - and all the things that are around you; “so that

things which are seen were not made of things which do

appear;”

the visible did not come from the

visible; it was not self-made.

God tells

you that.

Much more will this be felt, if we become personally

acquainted with God otherwise than through the medium of

His works. And

so, in fact, we do.

Even apart from revelation, - on natural principles, - the

first notion of a God is suggested in another way. It is

suggested far more promptly and directly

than it can be by a circuitous process of reasoning

respecting the proofs of

intelligence in creation.

It is

conscience within, not nature without, which first

points to and proves a

Deity. It

is the Lawgiver, and not the

Creator, that man first recognizes, - the Governor, the

righteous judge. The

moral sense involves the notion of a

moral Ruler, independently altogether of the argument

from creation. And

the true position and purpose of that

argument is not to infer from His works of creation an

unknown God as creator,

but to prove that the God already known as the moral

Ruler is the Creator of

all things, - or rather to show what, as the moral

Ruler, He has to tell us in

regard to the things which He has created.

The truth is, when we go to the works and

creatures of God, we go, not

to discover Him, but as having already discovered and

known Him. We

must, therefore, go in the spirit of

implicit and submissive faith, not to question them

concerning Him, but to hear

and observe what He has to say to us concerning them, or

to say to us, in them

concerning Himself.

But still further, we go now to the record of creation, not

only recognizing God through the evidence of His works

and the intimations of

the conscience or moral sense, but acquainted with Him

through the testimony of

His own word. In

that word, He reveals

Himself, first as the Lawgiver, and then as the Saviour. The first word

He spoke to man in paradise

was the law, the second was the glorious Gospel; He made

Himself known first as

the Sovereign, and then as the Redeemer.

Now, therefore, it is in the character of the God

thus known that He

speaks to us concerning the creation of all things; and

our faith as to

creation now consists. - not in our believing that all

things were and must

have been made by a God, - but in our believing that

they were made by this

God; and believing it on the ground of His own

infallible assurance, given

personally by Himself to us. This God we are to see in

all things. We

are to hear His voice saying to us, in

reference to every intended; and I am now telling you

that I did so.

Thus, by faith, we are to recognize, instead of a dim remote

abstraction, a real living being; personally present

with us, and speaking to

us of His works, as well as in them and by them.

We are to exercise a personal reliance on

Him, as thus present and thus speaking to us - a

reliance on His faithfulness,

in what He says to us concerning His character and

doings in creation.

Then assuredly our faith will make more

vividly and tangibly intelligible the great fact that He

made each thing and

all things, and will give to that fact more of a real

hold over us, and far

more of intense practical power, than, with our ordinary

vague views of the

subject, we can at all beforehand conceive.

Nor will it hamper or hinder the freest possible

inquiry, on the side of

natural science, if only it confines itself to its [Page 15] legitimate

function of ascertaining

facts before it theorises.

For the facts

it ascertains may modify, and have modified, the

interpretation put on what God

has told us in His word.

And He meant it

to be so. He

did not intend revelation

to supersede inquiry, and anticipate its results.

Of course, His revelation must be consistent

with the results of our inquiry, - as it has always

hitherto, in the long run,

been found to be. But

it was inevitable

that our understanding of His revelation should be open

to progressive

readjustment, as regards the development of scientific

knowledge, while the

revelation itself, as the Creator’s explanation of His

creation for all

mankind, remains ever the same.

4.

Thus, then, in a spiritual view, and

for spiritual purposes, the truth concerning God as the

Creator must be

received, not as a discovery of our own reason,

following a train of thought,

but as a direct communication from a real person, even

from the living and

present God. This

is not a merely

theoretical and artificial distinction.

It is practically most important.

Consider the subject of creation simply in the

light of an argument of

natural philosophy, and all is vague and dim

abstraction. It

may be close and cogent as a demonstration

in mathematics, but it is as cold and unreal; or, if

there be emotion at all,

it is but the emotion of a fine taste, and a sensibility

for the grand or the

lovely in nature and thought.

But

consider the momentous fact in the light of a direct

message from the Creator

Himself to you, - regard Him as standing near to you,

and Himself telling you,

personally and face to face, all that He did on that

wondrous creation-week, [restoration-week better!]

- are you not differently impressed

and affected?

(1) More particularly, - see first of all, what weight this

single idea, once truly and vividly realized, must add

to all the other

communications which He makes to us on other subjects. Does He speak

to us concerning other matters,

intimately touching our present and future weal [welfare]?

Does He tell us of our condition in respect of

Him, and of His purposes

in respect of us? Does

He enforce the

majesty of His law?

Does He press the

overtures of His Gospel?

Does He

threaten, or warn, or exhort, or encourage, or command,

or entreat, or tenderly

expostulate, or straitly and authoritatively charge? Oh! how in

every such case is His appeal enhanced

with tenfold intensity in its solemnity, its pathos, and

its power, if we

regard Him as in the very same breath expressly telling

us, - I who now speak

to you so earnestly and so affectionately, I created all

things, - I created

you. To the

sinner, whom He is seeking

out in his lost estate, whom He is reproving as a holy

lawgiver, and condemning

as a righteous judge, and yet pitying with all a

father’s unquenchable

compassion, how awful and yet how moving is the

consideration, that He who is

speaking to him as a counsellor and a friend, is

speaking to him also as the

Creator! And

while He bids the sinner,

in accents the most gracious, turn and live, He says to

him still always, - It

is thy Maker, and the Maker of all things, who bids

thee, at thy peril,

turn. And

is there any one of you who are His

saints and servants disquieted and cast down?

Is there not comfort in the thought, that thy

Maker is thy husband and

thy redeemer? Is

there not especial

comfort in His telling thee so Himself? Is there any

thing in all the earth to

make thee afraid? Dost

thou not hear Him

saying to thee, - I, [Page

16] thy

Saviour, thy God made thee, made

it, made all things?

It is my creature,

as thou art, and it cannot hurt thee, if I am with thee.

On this principle we may, to a large extent, explain the

importance which believers attach to the glorious fact,

that He who saves them

has revealed Himself to them, and is revealing Himself,

as the Creator. All

must have remarked, in reading the

devotional parts of the Bible, such as the book of

Psalms, how constantly the

psalmist comforts and strengthens himself, and animates

himself in the face of

his enemies, by this consideration, that his help comes

from the Lord, who made

the heavens and the earth, that his God made the

heavens. He

made all things; the very things,

therefore, that are most hostile and perilous, his God

made. This

is his security. The

God whom he knows as his own, made all

things, and is reminding him, whenever any thing alarms

or threatens him, that

He made it. And

if now, my Christian

brother, the God who made all things, evil as well as

good, - sickness, pain,

poverty, distress, - is your Saviour; if He is ever seen

by you, and His voice

is heard telling you, even of that which presently

afflicts you, that He made

it as He made you, - how complete is your confidence.

When God appeared to Job, in such a way that job himself

exclaimed, “I have heard of thee by the hearing

of the ear, but now

mine eye seeth thee;”

it was mainly, if not exclusively, as

the Creator that He revealed Himself.

Coming forth to finish the discussion between Job

and his friends, the

Lord enlarges and expatiates on all His wondrous works,

- on the power and the

majesty of His creation.

On this topic

He dwells, speaking to Job personally concerning it,

conversing with him face

to face as a friend.

And the full

recognition of God as doing so, is enough both to humble

and comfort the

patriarch, - to remove every cloud, - to abase him in

dust and ashes, - and to

exalt him again in all the confidence of prayer.

(2) Again, secondly, - on the other hand, observe what weight

this idea, if fully realized, must have, if we ever

regard the Lord Himself as personally

present, and saying to us, in special reference to each

of the things which He

has made, - I created it, and I am now reminding you,

and testifying to you,

that it was I who made it.

What

sacredness will this thought stamp on every object in

nature, - if only by the

power of the [Holy]

Spirit,

and through the belief of the

truth, we are made really and personally acquainted with

the living God; if we

know Him thus as the Lawgiver, the Saviour, the judge.

We go forth amid the glories and the beauties of this earth

and these heavens, which He has so marvellously framed. We are not

left merely to trace the dead and

empty footsteps which mark that He once was there. He is there

still, telling us even now that

His hand framed all that we see; and telling us why He

did so. Thus,

and thus only, do we walk with God,

amid all that is grand and lovely in the scene of

creation; not by rising, in

our sentimental dream of piety, to the notion of a

remote Creator, dimly seen

in His works, but by taking the Creator along with us,

whenever we enter into

these scenes, and seeing His works in Him.

It is true, there is a tongue in every breeze of

summer, a voice in

every song of the bird, a silent eloquence in every

green field and quiet

grove, which tell of God as the [Page

17]

great maker of them all; but after

all, they tell of Him as a God afar off, and still they

speak of Him as

secondary, merely, and supplementary to themselves, - as

if He were inferred

from them, and not they from Him.

But,

in our habit of mind, let this order be just reversed. Let us

conceive of God as telling us

concerning them as His works.

While they

reveal and interpret Him, let Him reveal and interpret

them. And

whenever we meet with any thing that

pleases our eye, and affects our heart, let us consider

God Himself, our God

and our Father, as informing us respecting that very

thing: I made it, - I made

it what it is, - I made it what it is for you.

And if this vivid impression of reality, in our recognition of

God as the Creator, would be salutary in our communing

with nature’s works,

much more would it be so in our use of nature’s manifold

gifts and bounties. “Every

creature of God is good, and

nothing to be

refused, if it be

received with thanksgiving;

for it is sanctified by the word

of God” (1 Tim.

4: 4,

5).

Still it is to be received and used as the

creature of God, and as

solemnly declared and attested to be so, by God Himself,

in the very moment of

our using it. If

we realized this

consideration; if, on the instant when we were about to

use, as we have been

wont, any of the creatures of God provided for our

accommodation, God Himself

were to appear personally present before us, and were to

say, Son, - Daughter,

- I created this thing which you are about to use, -

this cup of wine which you

are about to drink, this piece of money that you are

about to spend, this

brother or sister with whom you are now conversing, -

and I testify this to

you, at this particular moment, - I, your Lord and your

God, - I created them,

- such as they are, - for those ends which they are

plainly designed to serve;

- would we go on to make the very same use of the

creature that we intended to

make? Or

would not our hand be arrested,

and our mouth shut, and our spirit made to stand in awe,

so that we would not

sin?

Let none imagine that this is an ideal and fanciful state of

feeling. It

is really nothing more than

the true exercise of that faith by which “we understand that the worlds were

made by the word of God; so

that things which

are seen were not made of things which do appear;”

and

it is the preparation for the

scene which John saw in vision, when, being in the

Spirit, he beheld, and lo! a

throne was set in heaven, and one sat on the throne, and

round about the throne

the emblems of redeeming love appeared, with the

representatives of the

redeemed Church giving glory to Him that sat on the

throne, worshiping Him that

liveth forever and ever, casting their crowns before the

throne, and saying, “Thou art

worthy, 0 Lord,

to

receive glory, and

honour, and power;

for thou has

created all things, and

for thy pleasure they

are and were created” (Rev.

4).

My plan does not require me to enter at any length, if indeed

at all, into the vexed questions which have clustered

around the Mosaic cosmogony;

questions as to the relations of science and revelation

which I own myself

incompetent to discuss.

I have tried in

this Lecture to indicate the point of view from which,

as it seems to me, the

narrative in the first two chapters of Genesis ought to

be regarded. It

is God’s own account of the origin of the

present mundane system, given by inspiration, for all

times and for all

men. And it

is His account, specially

adapted by Himself to the [Page

18]

end, not of gratifying speculative

curiosity, but of promoting godly edification.

Therefore, there is purposely excluded from it

whatever might identify

it with any particular stage of advancement and

enlightenment among mankind.

It is this very exclusion, indeed, which

gives to it a breadth and universality fitting it

equally for all systems, as

well as for all ages.

Then again, as on

the one hand it is not the design of God to tell us here

all that we might wish

to have learned from Him respecting this earth’s long

past history, or even

respecting the adjustment of its present order, - so, on

the other hand, it is

His design to present this last topic to us chiefly in

its bearing on the great

scheme of providence, including probation and

redemption, which His revealed

word is meant to unfold.

He tells the

story of our birth only partially.

And

in telling it, He casts it in the mould that best adapts

it to that progressive

development of His moral government which His inspired

Scriptures are about to

trace.

Hence, amid dark obscurity hanging over many things, the

salient prominence given to the Word as the Light of the

world, its light of

life, - to the Spirit moving in the ancient chaos, - to

the satisfaction of the

Eternal at each step in the creative [restoration] work, - to the succession of six days and the rest of the

seventh.

And hence also, as regards man, the twofold account of his

origin, - that in the first chapter bringing out his

high and heavenly relation

to the Supreme, whose image he wears, and that in the

second chapter describing

rather his more earthly relations, and the functions of

his animal nature.

For these two accounts, so far from being

inconsistent with one another, are in reality the

complements of one another.

Both of them are essential to a complete

divinely - drawn portrait of man as at first he stood

forth among the

creatures; spiritually allied to God, in one view, yet

in another view, the

offspring as well as the lord of earth.

Both therefore appropriately culminate, - the one

in the Sabbatic

Institute, the pledge and means of man’s divine life, -

and the other in that

ordinance of marriage, peculiar to him alone, in which

his social earthly life

finds all its pure and holy joy.

These particulars will come up again for consideration. I

notice them now because I would like my first paper to

be studied as having an

important bearing on the subjects to which they relate.

*

*

*

CHAPTER 2

THE

CREATION OF THE WORLD AND MAN

VIEWED ON ITS HEAVENLY SIDE

Genesis 1:

1;

2:

3

This

divine

record of creation, remarkable for the most perfect

simplicity, has been sadly

complicated and embarrassed by the human [Page 19] theories and

speculations with which

it has unhappily become

entangled. To

clear the way, therefore,

at the outset, to get rid of many perplexities, and

leave the narrative

unencumbered for pious and practical uses, let its

limited design be fairly

understood, and let certain explanations be frankly

made.

1.

In the first place, the object of

this inspired cosmogony, or account of the world’s

origin, is not scientific

but religious. Hence

it was to be

expected that, while nothing contained in it could ever

be found really and in

the long run to contradict science, the gradual progress

of discovery might

give occasion for apparent temporary contradictions. The current

interpretation of the Divine

record, in such matters, will naturally, and indeed,

must necessarily,

accommodate itself to the actual state of scientific

knowledge and opinion at

the time; so that, when science takes a step in advance,

revelation may seem to

be left behind. The

remedy here is to be

found in the exercise of caution, forbearance, and

suspense, on the part both

of the student of Scripture and of the student of

science; and, so far as

Scripture is concerned, it is often safer and better to

dismiss or to qualify

old interpretations, than instantly to adopt new ones. Let the

student of science push his inquiries

still further, without too hastily assuming, in the

meantime, that the result

to which he has been brought demands a departure from

the plain sense of

Scripture; and let the student of Scripture give himself

to the exposition of

the narrative in its moral and spiritual application,

without prematurely

committing himself, or it, to the particular details or

principles of any

scientific school.

2.

Then again, in the second place, let

it be observed that the essential facts in this Divine

record are, - the recent

date assigned to the existence of man on the earth, the

previous preparation of

the earth for his habitation, the gradual nature of the

work, and the

distinction and succession of days during its progress. These are not,

and cannot be, impugned by any

scientific discoveries.

What

history of ages previous to that era

this globe may have engraved in its rocky bosom,

revealed or to be revealed by

the explosive force of its central fires, Scripture

does not say.

What

countless generations of

living organisms teemed in the chaotic-waters, or

brooded over the dark abyss,

it is not within the scope of the inspiring [Holy] Spirit to tell.

There is

room and space for whole

volumes of such matter, before the Holy Ghost takes up

the record. Nor is

it necessary to suppose that all continuity of the

animal life which had sprung

into being, in or out of the waters, was broken at the

time when the earth was

finally fashioned [or restored] for man’s abode. It is enough

that then, for the first time,

the animals of sea, and air, and land, with which man

was to be conversant, were

created for his use, - the fish, the fowls, the beasts,

which were to minister

to his enjoyment and to own his dominion.

3.

And finally, in the third place, let

it be borne in mind that the sacred

narrative of the creation is evidently, in its highest

character, moral,

spiritual, and prophetical.

The

original relation of man, as a responsible being, to his

Maker, is directly

taught; his restoration from moral chaos to spiritual

beauty is figuratively

represented; and

as a prophecy, it has an extent of meaning which

will be fully unfolded only when “the

times of the

restitution of all things” (Acts

3: 21)

have arrived.

Until then, we must [Page 20] be contented with a partial and

inadequate view of this, as of other parts of the sacred

volume; for “the sure

word of prophecy,” though a light “whereunto

we do well to take heed,” is still but “as a light shining in a dark place, until the day dawn

and the day-star arise in our hearts” (2

Peter 1: 19). The exact literal sense of much that is now obscure or doubtful, as

well as the bearing and importance of what may seem

insignificant or

irrelevant, will then clearly appear.

The creation [restoration] of this world anew, after its

final baptism of fire, will

be the best

comment on the history of its creation at first,

after the chaos of

water. The manner as well as the design of the earth’s formation of old out of

the water, will be understood at last, when it emerges

once more from the wreck

and ruin of the conflagration which yet awaits it, - “a new

earth, with new

heavens, wherein

righteousness is to dwell” (2

Pet. 3: 13).

Our present concern, therefore, is with the moral and spiritual aspect of this sacred narrative. Our business

is with man, - with

the position originally assigned to

him, by creation, in the primeval kingdom of nature,

and the place to which he

is restored, by redemption, in the remedial kingdom of

grace. Of his

abode in the renewed kingdom of glory, it is but

the shadowy outline which

we can in the meantime trace; but, so far as it goes, it

is interesting and

suggestive.

Thus, then, let us view the scene which the opening section of

Genesis presents to us.

There is a plain

distinction

between the first verse and the subsequent part of

this passage.

The first verse speaks of creation, strictly so

called, and of the

creation of all things, - the formation of the

substance, or matter, of the

heavens and the earth, out of nothing; - “In the beginning God created the

heavens and the earth.” The rest of the passage speaks of creation in the less exact sense of

the term; describing the changes wrought on matter

previously existing; and it

confines itself, apparently, to one part of the

universe - our solar system,

and especially to this one planet - our earth,

concerning which, chiefly, God

sees fit to inform us.

The first verse, then, contains a very general announcement;

in respect of time, without date, - in respect of space,

without limits. The

expression, “in the

beginning,”

fixes

no period; and the expression, “the

heavens and the

earth,” admits of no restriction.

For, though heaven denotes sometimes the

atmosphere, or the visible

starry expanse above, and, at other times, the

dwelling-place of God and of the

blessed; yet, when heaven and earth are joined, as in

this text, all things are

evidently intended (Ps.

131: [1], 2,

etc.)

And the announcement here is, that at an era

indefinitely remote, the

whole matter of the universe was called into being. It is not

eternal, - it had a beginning.

God has not merely, in the long course of

ages, wrought wonderful changes on matter previously

existing. Originally,

and at the first, He made the

matter itself.

At the period referred to in the second verse, the materials

for the fair structure of this world which we inhabit

are in being. But

they are lying waste.

Three things

are wanted to render the earth such as God can approve ‑

order, life, and

light. The

earth is [or ‘became’,

N.I.V.] “without form” -

a shapeless mass.

It is [or became] “void,” - empty, or destitute

of life. It

has “darkness” all [Page

21]

around its deep chaotic “waters.” One

good sign only appears.

There is a movement

on the surface, but deep-searching.

“The Spirit of

God moved on the face of the waters.”

We have here the first

indication in the Bible of a plurality of Persons in

the unity of the Godhead;

and, in the chapter throughout we

trace the same great and glorious doctrine of the

ever-blessed Trinity,

pervading the entire narrative.

This

truth, indeed, is not so much directly stated in the

Scriptures as it is all

along assumed; and we might reasonably expect it to be

so. God is

not, in the written word, introduced

for the first time to men.

He speaks,

and is spoken of, as one previously known, because

previously revealed.

And, if the doctrine of the Trinity be true,

He must have been known, more or less explicitly, as

Father, Son, and Holy

Ghost. An

express and formal

declaration, then, of this mystery of His being, was not

needed, now was it to

be expected. The most natural and convincing proof of

it, in these

circumstances, is to trace it, as from the very first

taken for granted and

recognized, in all that is said of the divine

proceedings. Now,

in this passage, we find precisely such

intimations of it as might have been anticipated.

Not to speak of the form of the word “God,”

which, in the original, is a plural noun joined

to a singular verb, we have the remarkable phrase (ver. 26), “Let

us make;” and, in the

very outset, we have

mention made of God; - of His WORD,

“God said:” - and of His

Spirit, “the Spirit

of God moved.”

So,

also, it is said, in the Psalms (33:

6), “By the word of the Lord were the heavens made, and all the hosts of them

by the breath,” or Spirit, “of his mouth.”

The gradual process by which the earth is brought into a right state may be traced according to the

division of days. But

there is another

principle of division, very simple and beautiful,

suggested by the repeated

expression, “God saw that it was good.”

That

expression may be regarded

as marking the successive steps or stages of the

divine work, at which the

Creator pauses, that He may dwell on each finished

portion, as at last He

dwells on the finished whole, with a holy and

benevolent complacency.

The phrase occurs seven times (ver. 4,

10, 12,

18, 21,

25, 31).

It does not divide the work exactly as the days

divide it. On

the second day it does not occur at all;

and on the third

and sixth days it

occurs twice.

The work is divided

among the days,

so that each day has

something definite to be done, - something complete in

itself. 1.

Light, - 2.

Air (the elastic

firmament or sky), - 3.

Earth (dry

land as separated from the sea), - 4.

the Luminaries in heaven as means of light and measures

of time, - 5.

Fish* and Fowl, - 6. Beasts, and Man himself, - these are the works of the successive days.

The relation, however, of the several parts to

the whole, is better seen

by noting the points at which the divine expression of

satisfaction is

inserted: “God

saw that it was good.”

[* Note.

Our Lord’s use of the “two

fishes,” in

feeding the multitude, may well have been a “sign”

= ‘miracle’ -

to point His disciples toward the time of God’s

promised millennial

blessing, after their sojourn in “paradise”

-

(the place of the souls of the dead) - for a further two days. That is,

after two

thousand years, they would be brought back

here to enjoy their inheritance.

This can only be possible after the time of

their Resurrection from

the dead.

See, - Matt. 14:

17, 19;

Luke 22: 29,

30; 23:

43; 2

Pet. 3: 8, 9;

Phil. 3:

11; Rev.

20: 4-6.]

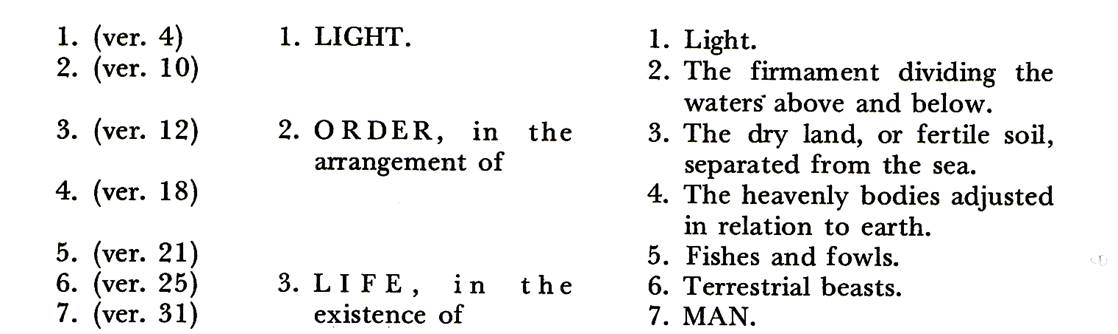

The main design of the whole work is to supply the wants or

defects of the chaotic earth. These

were three: - the want of order, of

life, and of light.

Light is first

provided; then order is given that the earth may be

fitted for the habitation

of living creatures; and finally, living creatures are

placed in it.

[Page 22]

Now, the series

of operations by which

this threefold object is accomplished, is

exactly marked by the

intervals at which it is said, “God

saw that it was

good.”

Thus, 1.

On the introduction of LIGHT,

which is a simple act, the

Creator’s joy is expressed emphatically, but only once (ver 4). 2.

The ORDERING of the world, however, is a more complicated and elaborate

process. In

the first place, there must

be the adjustment of the waters; that is, on the one

hand the separation of the

cloudy vapour constituting the material heavens above,

from the waters on the

earth’s surface below, by the air, or elastic

atmosphere, being interposed; and

on the other hand, the separation on the earth’s surface

of the dry land from

the sea. Secondly,

there must be the

arrangement of the dry land itself, which is to be

clothed with all manner of

vegetation, and stored with all sorts of reproductive

trees and plants. And

thirdly, there must be the establishment

of the right relation which the heavens and the heavenly

bodies are to have to

the earth as the instruments of its light, and the

rulers of its seasons.

Accordingly, at each of these three stages of

this part of the work, - the reducing of the shapeless

mass of earth to ORDER

– the language of divine

approbation is employed (ver.

10, 12,

18).

3.

The formation of LIFE

also, or of the living beings for

whose use the world is made, - admits of a similar

sub-division. First,

the fishes and the fowls are produced;

secondly, the terrestrial beasts; and thirdly, man

himself. And

still, as the glorious work rises higher

and higher, there is at each step the pause of divine

congratulation; as, in

the end and over all, there is the full contentment of

Infinite Wisdom; “rejoicing in

the habitable parts of the earth, his

delights

being with the sons of men” (ver.

21;

25, 31,

and Prov. 8:

31).

The

following scheme will show this division clearly:

God

saw that it was good on the

production of -

1.The

first step in this glorious

process, is the breaking in of LIGHT

on the gloom in which the earth was shrouded (ver.

3-5). In this step

the ETERNAL WORD

comes forth from the bosom of Deity.

He “whose goings forth have been from of

old, from everlasting”

(Mic.

5: 2),

-

“the Word

who was in the beginning with

God and

was God” (Jn.

1: 1-3), -

He is that word which went out from God, when “GOD SAID, Let

there be

light.” For this

is not the utterance of a

dead sentence, but the coming forth of the living

WORD.

In the Word was life, and this

life in the Word, - this LIVING

WORD,

- was the “light.” Immediately, without the intervention of those luminaries in which

afterwards light was stored and centered, the LIVING

WORD Himself going forth was

light, - the

natural light of the earth

then: as afterwards, again coming forth, He became to

men the light of their

salvation.

[Page 23]

In this light God delighted as good; for the light is none

other than that very Eternal Wisdom who says; ‑ “The LORD

possessed me in the beginning of

his way, before his

works of old, and I

was daily,” - from day to day, as the

marvellous

work [of His

restoration] of these six days went on, - “I was daily his

delight, rejoicing

always before him” (Prov.

8: 22,

30). Such

was the mutual ineffable complacency of

the Godhead, when the Word went forth in the creation,

as the light, and when

all things began to be made by Him (Jn.

1: 3,

4).

And in

this first going forth of the Eternal Word, the

distinction of light and darkness,

of day and night, for the new earth, began (Ps.

104: 2). This was the

first day - the first

alternation of evening and morning; - not

perhaps the first revolution

of this globe on its axis, but its first revolution,

after its chaotic darkness, under the

beams of that divine light, which, shining on earth’s

surface as it passed

beneath the glorious brightness, chased, from point to

point, the ancient gloom

away.

2.

To light succeeds ORDER.

Form, or shape, or due arrangement, is given to

the natural economy of

this lower world, and that by three successive

processes.

(1) In the first place, the waters are arranged (ver.

6-10). The

earth is girt round with a firmament, or gaseous

atmosphere; at once pressing

down, by its weight, the waters on the surface, and

supporting, by its

elasticity, the floating clouds and vapours above; and

so forming the visible

heaven, or the azure sky (Ps.

104:

3). This

is the work of the second day.

Then, a bed is made for the waters, which

before covered the earth, but which now, subsiding into

the place prepared for

them, lay bare a surface of dry land (Ps.

104: 6-13).

This

is done on the third day.

And thus, by a

twofold process, the waters are reduced to order.

In the language of Job, “He girdeth up

the waters in his thick clouds; and

the cloud is

not rent under them: he

holdeth back the face of

his throne, and

spreadeth his cloud upon it.”

This

surely must allude to the separating of the waters above

the firmament from the waters under the firmament. And as to

these last, the description

proceeds, “He hath compassed the waters with

bounds, until the day

and night come to an end” (Job

26: 8-10). So, also, in

another

place, the Lord, challenging vain man to answer Him,

asks, “Who shut up

the sea with doors, when

it brake forth as if it

had issued out of the womb; when

I made the

cloud the garment thereof, and

thick darkness a

swaddling band for it?” Here we have plainly the

firmament

dividing the waters. And

I “brake up for

it,”

for the sea

that once covered the earth, “my decreed place, and

set

bars and doors, and

said, Hitherto shalt

thou come, but

no farther; and here

shall thy proud waves be

stayed.” Here we have

with equal plainness the gathering

together of the waters and the appearing of the dry land

(Job 38: 8-11).

The

same twofold process in disposing of the waters is

indicated by the psalmist; -

“0

give thanks therefore to him, that

by his Wisdom

made the heavens, for

his mercy endureth forever”

(Psa. 136:

5, 6); - and by the

Apostle Peter; - “By the word

of the Lord, the

heavens were of old, and

the earth, standing

out of

the water and in the water” (2

Pet. 3: 5).

(3) In the third place, on the fourth day, the heavenly

bodies, in their relation to this earth, are formed or

adjusted. The

light, hitherto supplied by the immediate

presence of the WORD,

which had gone

forth on the first day - the very Glory of the Lord,

which long afterwards

shone in the [Page

24]

wilderness, in the temple, and on the

Mount of Transfiguration, and which may [will] yet again illumine the world - the light, thus originally

provided without created instrumentality, by the LIVING WORD Himself, now that the chaotic mists are cleared away

from

the earth’s surface, is to be henceforward dispensed

through the natural agency

of second causes. A

subordinate fountain

and storehouse of light is found for the earth.

The light is now concentrated in the sun, as its

source, and in the moon

and stars, which reflect the sun’s beams; and these

luminaries, by their fixed

order, are made to rule and regulate all movements here

below (Ps. 104:

19-23). They

are

appointed “for signs,”

- not for tokens

of divination (Isa. 44:

25; Jer.

10: 2),

- but

for marks and indications of the changes that go on in

the natural world; - and

“for seasons,” - for the

distinction of day and

night, of summer and winter, seed-time and harvest (Jer.

31: 35). Again,

therefore, let us “give thanks

to him that made great lights, for

his mercy

endureth forever; the

sun to rule by day,

for his mercy endureth forever;

the moon and stars to rule by

night, for his mercy

endureth forever” (Ps.

86: 7-9).

Thus, all things are ready for living beings to be formed -

those

living beings which belong to the social economy of

which MAN is head.

3.

Accordingly, LIFE - life in abundance - is now produced.

For the Eternal

Word, or Wisdom

(Prov. 8:

22-31),

in the

whole of this work of creation, in which He was

intimately present with the

Father, rejoiced especially in the earth as habitable;

and above all, “his delights

were with the sons of men.” In the first

place, in

the waters, and from the waters, He causes fishes and

fowls to spring: - fishes

to move in the bosom of the sea, and fowls to float in

the liquid air and fly

abroad in the open firmament of heaven.

This He does on the fifth day (ver.

20-33). Secondly, on

the sixth, He causeth all beasts

to be produced from the earth (ver.

24, 25). And, in the

third place, on the sixth day

also, He creates MAN

(ver. 26,

27).

These three orders or classes of living beings are severally

pronounced good, But man is specially blessed (ver.

26, 27). There is

deliberation in heaven respecting

His creation: “Let us

make man.”

He is

created after a high model – “after our

likeness.”

He

is invested with dominion over the

creatures: “Let them have dominion over the fish

of the sea, and over

every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.”

He is formed for

holy matrimony, for dwelling

in families: “male and female” - one male and one female - “created he them.”

Thus, in four particulars, is man exalted above the other

animals. In

the first place, the

counsels of the Godhead have respect to man.

To his creation, as well as to his redemption,

the Father, the Son, and

the Holy Ghost consent.

Then, secondly,

the image of God is reflected in him, - in his capacity

of intelligence, his

uprightness of condition, and his immaculate purity of

character, - in his

knowledge, righteousness, and holiness (Eph.

4: 24;

Col. 3:

10).

A

third distinction is, that the other animals are

subjected to him, - not

to his tyranny as now, but to his mild

and holy rule; - as they shall be when sinners are

consumed out of the earth,

and the wicked are no more (Ps.

54: 35;

8: 6-8; Rom.

8: 20-22).

While his fourth and final [Page

25]

privilege is, that marriage, and all

its attendant blessings of society, are ordained for

him. This

the prophet Malachi testifies, when, sternly rebuking his countrymen for the

prevailing sin of adultery and the light use of divorce,

he appeals against the

man who shall “deal treacherously with the wife of

his youth,” – “his

companion and the wife of his covenant,” - to the

original design and purpose

of God in creation. “Did

not he make one?”

- a

single pair, - “yet had he

the residue of the spirit,” - the excellency or abundance of the breath of life. “Wherefore,

then, did

he make one?”

- limiting Himself to the creation of

a single pair? - “That he might seek a goodly seed,” - or in other

words, that holy

matrimony, - based upon the creation of the one male and

the one female, and

the destination of them to be “one flesh,” - might purify and bless the social state of man (Mal. 2:

14-16).

Such was the primitive constitution of life in this

world. Man

stood forth, godlike and

social, having under him, as in God’s stead, all the

creatures; and for his

life, and for theirs, that food was appointed which the

earth was to bring

forth (ver. 29,

30).

The two previous stages in the creation are

subservient to this

last. Light

and order are means, in

order to life, which is the end.

Life -

animal, intellectual, moral, spiritual, social, divine -

life is the crown and

consummation of all.

The Creator beholds

it, and is satisfied, and rests.

“Thus the heavens and the earth were

finished, and all the

host of them.

And on the seventh

day God ended his work which he had made; and he rested on the seventh day from all his work which he had made. And

God blessed the

seventh day,

and sanctified it;

because that in

it

he had rested from all his work which God

created and made” (Gen.

2: 1-3).

The rest of God is not

physical

repose after weariness or fatigue, nor is it absolute

inactivity.

During all the period of His rest, from that

first day of rest downwards

until now, He worketh still (John

5: 17); and

He must continually work for the

continual preservation of His creatures (Ps.

104: 28,

29).

But He

pauses from His work of creation, - from the creation of

new kinds and orders

of beings; though He still carries on His work of

providence. He

rests from all His work which He has

made. He

rests and is “refreshed”

(Exod. 31:

17). And His original

day

of rest is blessed and sanctified.

Into the rest of God, with all its blessedness and sanctity,

man at first might enter; and hence the seventh day, as

the day which was the

beginning of the rest of God, became the “Sabbath made for man” (Exod. 20: 11;

Mark 2: 27).

To the people of God still, in every age, there is a

promise left, that they shall again enter into his

rest.

And the

promise is still

subsisting. For

the rest of

[Page 26]

Such is the

unanswerable reasoning, as it would seem of the inspired

apostle, founded upon

the Lord’s appeal to the Israelites,

when He exhorts

them to hear His voice.

“Harden not your heart,” is the voice of

God, their Maker, “as your fathers

did, who provoked me

in the wilderness, and to whom I sware

in my wrath that they should not enter into my rest.” Harden not your hearts, lest you also come short of that [future] rest. But were not they who were thus

addressed already in possession of that rest into which

God sware that their

fathers should not enter?

Certainly

they were, [with the exception the accountable

generation who perished in the wilderness] if that rest was the rest of

Now this [future] rest has been long prepared. For

“the works were finished from the

foundation of the

world; and he

spake

in a certain place of the seventh day on this wise,

and God did rest on the

seventh day from all his works” (Heb.

4: 3,

4).

Of this original rest it is, and not of any

image

of it afterwards appointed, that God speaks when He

says, “If they shall enter into my rest.” No rest hitherto given on earth, either by Joshua to the Old Testament

Church, or by Jesus to the New, is or can be the rest

of God, into which His

people, if they come not short through unbelief, are

to enter. That

rest remaineth for them, after they have

ceased from their works, as God did from His (Heb.

4: 10). And the type

or pledge of it remaineth also;

- perpetual and unchangeable, as the promise of the rest

itself; - the type and

pledge of it, instituted from the beginning, in the

hallowed rest of the weekly

Sabbath.

Through the help of this Sabbatic Institution, if only we

obtain a spiritual and sympathizing insight into its

significancy, we may enter

into the rest of God by faith, and in the spirit, even

now, as we realize the

blessed complacency of the Creator, rejoicing in his

works.

Pause, therefore, 0 my soul! at every stage of the wondrous

process

here described, and especially at its close; and behold

how good it is! See

how all was fitted for thee; and what a

being art thou, so fearfully and wonderfully made (Ps.

139: 14);

thyself

a little world; and for thy sake this great world made! How marvellous

are God’s works! How

precious also are thy thoughts unto me, 0

God! Let me

see, as God saw, everything

which He has made.

Behold, it is very

good. And

blessed and joyful is the rest

which succeeds.

Man, however, who was [created to wear] the

crown, has become the curse of

this earth.

[Page 27]

The work of God has been destroyed; and He must create

anew. And

it is, first of all, man

himself that He must remodel and reform. The

chaos now is not in matter but in mind,

- not in the substance of this earth, but in the soul of

man. In

that world now there is darkness,

disorder, death. But

“in the WORD

is

life.”

And, in the first place, “the life is

the light of men.”

He shines into

the darkened understanding, and all is light – “For God, who

commanded the light to shine out of darkness, hath shined in our hearts, to

give the light of the knowledge

of the glory

of God

in the face of Jesus Christ”

(2 Cor.

4: 6).

The glory of God, the true and living God, is

seen in the Living

Incarnate Word, the man Christ Jesus, the light of life,

the author of

salvation. “I have heard of thee with the

hearing of the ear, but

now mine eyes seeth thee” (Job 42: 5)

- seeth thee in Christ, the Holy One,

the just, the Saviour.