Remarks on the Prophetic Visions

in the Book of Daniel

By

S. P. TREGELLES, L.L.D.

Seventh Edition, 1965

When ye therefore

shall see the abomination of desolation, spoken of by Daniel the prophet, stand

in the holy place, whoso readeth, let him understand.

-------

PREFACE

TO THE

FOURTH EDITION

The Remarks on the Prophecies in Daniel, contained

in the following pages, originally appeared in separate portions, at different

times, from 1845 to 1847. They were then

printed and published just as I had time to prepare them from the notes with

which was furnished, which had been carefully and efficiently taken whilst I went

through these portions of prophecy orally with some Christian friends. My work of preparation, from the notes which

were put into my hands for the purpose, was

carried on while I had but little access to books of reference, and thus I

could give my “Remarks” no such complete

revision as I could have wished.

When the last of the separate parts appeared, the

whole was published in one volume, which has twice been reprinted, just as it

was, to meet an existing demand, without however any revision on my part, or I

believe any intentional alteration.

These three impressions having been out of print for

some time, I was requested to publish a new edition, but I was unwilling that

the book should be again printed without giving to the whole that careful and

thorough revision which ought to be bestowed on everything relating to those

truths which God has taught in His word.

I have, therefore, examined every part with Scripture; and although the

alterations in the statements of the “Remarks” are but few, yet here and there

various additions have been made, such as appeared to me to be either needful

or desirable. It has thus been during

more than two years under my hand, at times, for the purpose of this revision.

To the original “Remarks”,

as first published, I have now added so much as almost to make this to be a new book. It contains all that was published before,

but with more than an equal quantity in addition of what is new.

The principal material enlargements have been in the “Note on

the Year-day System” (which has now extended to a whole chapter,

in order to consider the subject fully), the “Note on

the Interpretation of Daniel 11 by past History”, and the “Note on Prophetic Interpretation in Connection with Popery

and the Corruption of Christianity.” In this last-mentioned Note I have now

endeavoured fully to show how the word of God meets Romish and non-evangelical

error, and that the simple application of Scripture, as literally understood,

does not in any sense palliate Popery, whether regarded in its doctrines or its

practices.

It is not, I believe, needful to specify the minor

enlargements and alterations throughout the “Remarks”,

they have been introduced without making any change in the general principles

as to the explanation of Daniel, or in their application to particular details.

The “Note on the Roman

Empire and its Divisions” is entirely an addition.

In “Concluding Remarks”

I have stated some particulars relative to the origin of the following pages,

and also spoken of some of the dangers against which students of prophecy do

well to be on their guard.

The “Map of the Ancient

Persian and Roman Empires”, and the “Explanatory

Notice”, are also amongst the additions now made.

The reader will perceive that my “Remarks” are so connected with the portions of

Scripture to which they relate, that, for them to be rightly followed, the

Bible should be kept open for continual reference.

I believe that these “Remarks”

have already been found of use to some, in their endeavours to know what is

taught us in the word of God. That they

may continue to be blessed to this end is my earnest desire and prayer. Whatever leads us simply to the Scripture,

which is the testimony of the Holy Ghost concerning Jesus Christ our Lord, in

His sufferings and in His glory, may be known by our souls as replete with

establishment in the apprehension of His truth and grace.

If readers, who pass by all Prefaces, find

themselves on good terms with the books they read, authors perhaps have no

right to complain; but as with our friends, so with our books; might not many

mistakes be avoided, and after-explanations be rendered needless, if we took

care not to overlook the conventional ceremony of an introduction?

- S. P.

T. Plymouth, August 15, 1852.

* *

* * *

* *

In issuing a fresh reprint of this volume no

alteration has been made beyond mere verbal corrections and occasionally the

addition of a brief note or of a few words; an Alphabetical Index has also been

added. I have not judged it best to make

allusions to works on the subject which have appeared since 1852: I have not,

however, neglected them; though in no case have I seen it needful to change the

views previously expressed; indeed, on many points they have been materially

confirmed. I had two reasons for not

discussing the opinions expressed in more recent works; the one is that such

discussions would so add to the bulk of the volume as to change its character,

which unless it were needful I did not wish: the other is that it would have

been too great a demand on my time and attention, seeing that it is not right

for me to do anything which would materially interfere with that work in which

I have specially to seek to serve the Church of Christ; I mean the Greek Testament

on Ancient Authorities, for which I have collated every accessible ancient

Greek document, and of which the four Gospels were some time ago completed,

before I was compelled by seriously impaired health to lay aside my work for a

time.

It is not for those who value the word of God to

shut their eyes to the condition of things in the professing Church. On the one side we find the sacrifice of

Christ owned as a fact, but its application to us is made to depend on

ecclesiastical ordinances and not on the operation of the Holy Ghost in leading

the soul of the sinner to the blood of the Cross: on the other hand there are

those who would own Christ (and in word perhaps the Holy Ghost) as acting on

the soul, and thus they speak of our deliverance by a Redemption in power by a

living Saviour, while redemption by price paid, a perfect propitiation wrought

out once and for ever by the death of Christ, is utterly ignored and even

denied. Thus on either side the truth of

God is rejected; but what rejection equals that in which the Cross of Christ is

not allowed its true place? that in which “sacrifice”,

“shedding of blood for the remission of sin”,

etc., are words only (if owned at all), and not substantive realities?

It has been a portent amongst us that those in

office and profession holding the place of Christian teachers have even set

themselves to argue against the very books of Holy Scripture which they were

bound to maintain, and which are commended to us with all the authority of the

incarnate Son of God.* Such attacks had been but little expected,

except from those not professing to be under the banner of the Lord Jesus.

[*

Under the guise of courtesy we often now find a willingness to concede to

opposers almost every vital point: so that professed defenders of the authority of Holy Scripture themselves give up,

and commend others for giving up the absolutely decisive teaching of the Lord

Jesus Christ and of the Holy Ghost, through the Apostles, as to questions of

simple fact. Thus one who has professed

to vindicate the Pentateuch as to its historic character has been commended in

that he “very wisely declines to avail himself of the

testimony of the New Testament in his attempt to prove the historic character

or Mosaic origin of the Pentateuch. The

use that has been made in this controversy of the supposed testimony of Jesus

Christ is for the purposes of general criticism wholly irrelevant. It involves certain theological hypotheses

which would be rejected by very many who are unquestionably orthodox, and to a

reverent piety it is every way offensive. Nothing can be more impolitic (to put

the matter on the very lowest ground) than to make the Divine wisdom of our

Lord responsible for those canons of criticism and literary opinions which are

notoriously uncertain, fluctuating, and progressive”, etc. If professed defenders can thus write, what line of demarcation remains between

truth and error? If our Lord’s own

statements are but a “supposed testimony”, on

what can we rely? We have not to make

our Lord’s Divine wisdom responsible for any uncertain, fluctuating, and

progressive canons of criticism, but we have to subject our notions on such

subjects to His divine teaching. If we

are not to believe Him when He said “Moses wrote of me”,

if we may doubt His wisdom and truth in saying this, then (and not till then)

we may be Christians of “reverent piety”,

though rejecting alike the writings of Moses and the words of Jesus. It is not surprising that those who set aside

the reality of our Lord’s work of propitiatory sacrifice should contemn first

the law in which sacrifice is so taught, and then our Lord Himself as an

authoritative teacher.]

Also, in that which professes to be the true

spiritual part of Christ’s Church, what laxity do we find! All that I said in the conclusion of this

volume as to Definite Confessions of faith has a tenfold force now. New things seem so opposed by some who make

pretensions to the holding of Evangelical truth as the doctrine of Scripture

(so firmly held by the Reformers) of our acceptance in the imputed

righteousness of our Lord Jesus Christ.

They admit anything rather than that He so kept the Law for us that His

living obedience is put down to the account of every sinner who is cleansed in

His blood. This is one way in which

Christ’s real substitution is set aside: He obeyed for us meritoriously

in His life, even as He suffered penally for us in His death. But the reality of His incarnation (as set

forth in all the old and orthodox confessions) is opposed by those who either

deny the true sacrifice of the cross or who contradict the true doctrine of

imputation. The Lord in His life obeyed

the Law, and it is in vain to contemn such living obedience by asking if it was

“mere law fulfilling”: for if Jesus did ever

and in all things obey the Law, loving the Lord His God with all His heart and

with all His mind and soul, and strength, then was His whole life a righteous

law-fulfilling, beyond which He could not go: and by God’s grace, “Christ is the end of the law for righteousness to every one

that believeth”. But in fact

those who suggest such doubts seem not to know what is meant by the holiness of

God, the law of God, the one obedience by which many shall be constituted

righteous; and they only confuse the unwary by some new and false notions on

the whole subject of substitution and sacrifice as a sweet savour before God.

But the denial of a doctrine of God does not make it the less true and

precious, or its maintenance of the less importance.

- S. P. T. Plymouth, July 9, 1863.

* *

* * *

* *

PEFACE

TO THE SEVENTH EDITION

First published in 1852. The last hundred years have seen six editions

of this invaluable book, revised and amplified by the author. The sixth edition has been in demand since

his death and through two World Wars has informed and instructed Christians in

the sure word of prophecy. Mr G. H. Lang in his various books

recommended it highly; and C. H.

Spurgeon in his ‘Commenting and Commentaries’ said

of the book ‘Tregelles is deservedly regarded as a

great authority upon prophetical subjects’. The S.G.A.T.

Council recommends it today. The last,

long chapter on a ‘Defence of the authenticity of the Book of

Daniel’ has been omitted, not because of any disagreement but

for economic reasons and because no prophetic student today has any doubts

about the subject in view of our Lord’s endorsement. An appendix has been added

on the life and works of Dr. Tregelles.

* *

* *

* * *

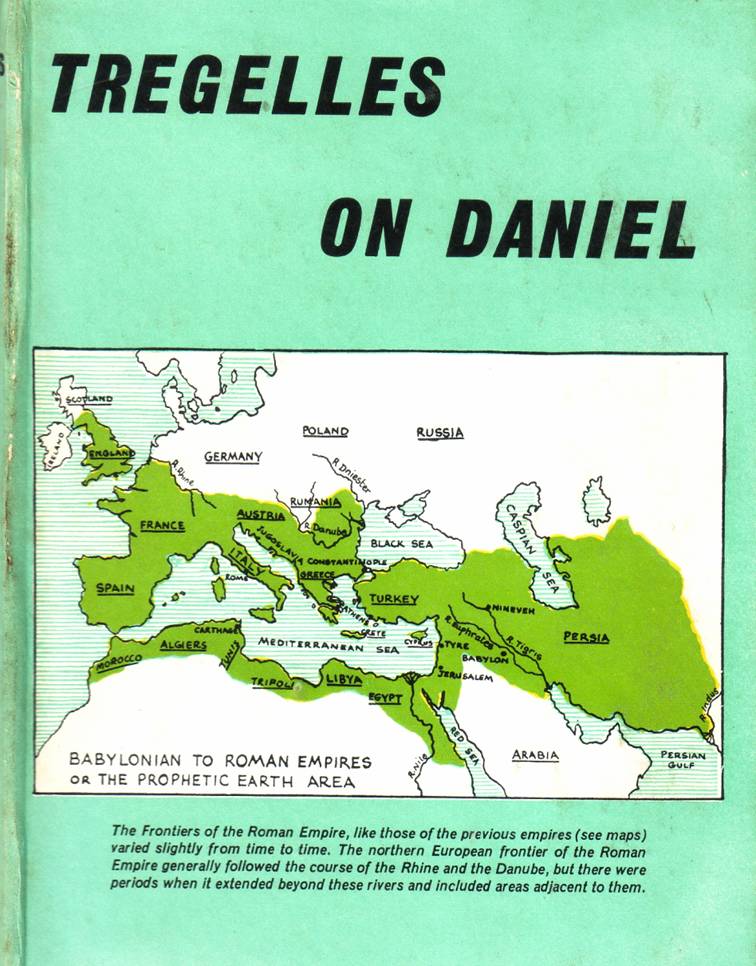

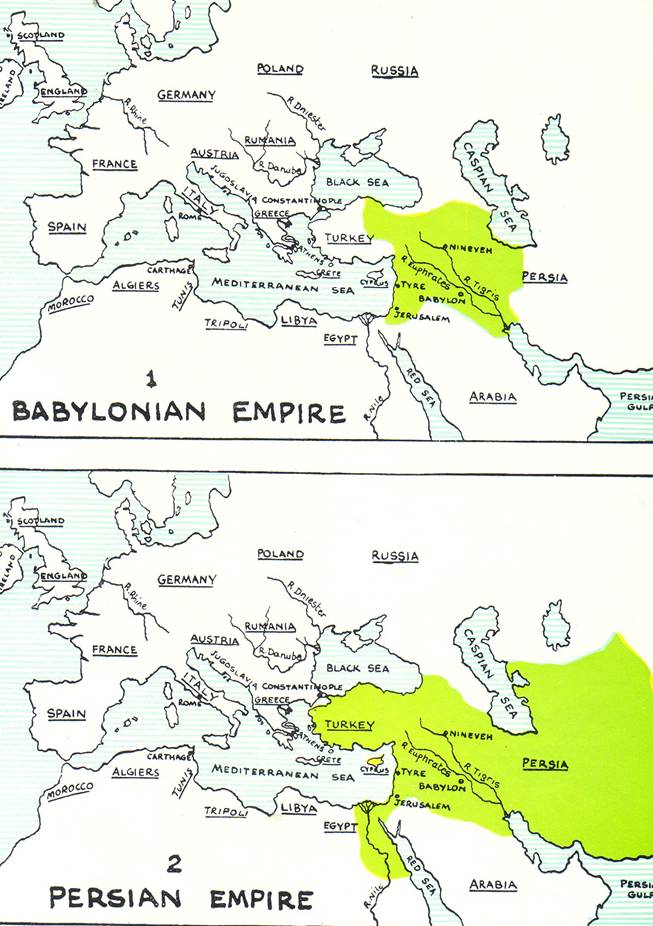

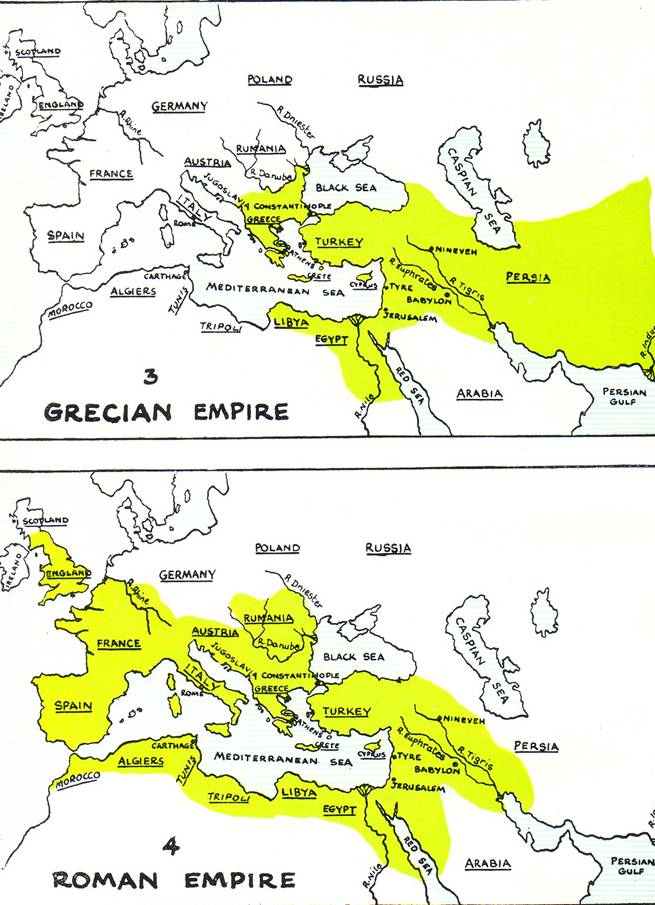

NOTE

DESCRIPTIVE OF THE

MAPS OF THE

ANCIENT EMPIRES OF PROPHECY

These maps have been introduced as showing the

extent of the territory to which the prophecies of Daniel refer: these ancient

empires are exhibited on the same scale.

So that they may at once be easily compared.

The limits of the Babylonian monarchy, under

Nebuchadnezzar, cannot be defined with certainty; besides the territory which

he actually held, there was also,

in all probability, a large extent of country under his sway and influence,

although actually governed by subordinate sovereigns. The territory of the Medo-Persian kings is

accurately known. It must however be

borne in mind that the Persian empire comprised large districts of mountain and

desert, and that the provinces, separated by such regions, often owned a very

partial allegiance to a monarch ruling in

Susa or Ecbatana. There were also

districts which, though lying within the Persian monarchy, were governed by vassal kings.

For many years before the reign of the last Darius

the Perersian empire was materially weakened; whole provinces cast off their

allegiance, and if reduced at all, it was to a very doubtful submission. Thus the conquests of Alexander gave him not

only a more extensive territory than that of the Persian kings, but also a

sovereignty more truly under his sway. The four kingdoms which were formed out

of Alexander’s empire are defined, page 79.

Of these, that of Seleucus was by far the largest, but much of its

extent was not retained by his successors; the eastern provinces became

independent, and in other parts, such as

The

These maps were supplied by Bishop D.A. Thompson, as used in his booklet “TheVisions & Prophecies of Daniel

Illustrated.”

-------

THE FOUR EMPIRES OF DANIEL

(Chapters 2, 7, & 8.

At one time

-------

INTRODUCTION [Pages 1-5]

THE BUDDING OF THE FIG-TREE

“Now learn a parable of the fig-tree: When his branch is yet

tender and putteth forth leaves, ye know that summer is nigh: so likewise ye,

when ye shall see all these things, know that it is near, even at the doors”

(Matt. 24: 32, 33).

In this instruction of our Lord to His disciples He shows them

the manner in which their expectation was to be directed to coming events. He had told them of the condition of things,

in connection with

Centuries have passed since the discourse on the

It may be said, What use can it have

been to the Church to have had to wait for so many years? What profit is there to us in being directed

to that which for eighteen hundred years has not taken place? If Christ has commanded it, that is enough -

He will always vouchsafe blessing to those who are doers of His will - but

further, here is profit which a spiritual mind can apprehend; for if this word

had been heeded by saints, it would have kept them from many of those

associations and objects which are contrary to the leadings of the Spirit: for

thus they would have had before their minds the character and close of this

dispensation, and the place of Christ’s faithful servants in the midst of the

nations, holding the gospel of the kingdom as a witness, but seeing the world’s

corruption as a thing which flows on unchanged in its nature (while souls are

gathered one by one out of it), even up to the coming of the Lord Himself. Had this exhortation been rightly heeded, the

hope of the coming of Christ would not have passed away from the minds of

saints, so as to be looked at as a thing which, at all events, is not a

practical doctrine.

Suppose I were cast upon some uninhabited isle, in a clime in

which I could not (from my ignorance of its situation) count the seasons by

months; and if the object of my hopes was the summer, and I found a fig-tree,

and knew that its budding forth would intimate the approach of that

season. I should watch the tree; I

should often examine whether it was beginning to bud forth. I might look week after week and see nothing;

I might think I saw some indications of sprouting, and

then find it all come to nothing, but still I should watch on. Now, if I also

knew that a ship came to the island at a particular time in the summer, this would

be a point of hope to me, for it would hold out the prospect of deliverance;

and this would make me doubly diligent in watching and waiting for the

budding. Hope would connect itself with

those things which indicate its accomplishment.

And these things occupying my mind, I should be preserved from the

thought of regarding the solitary isle as my abode. I might find long patience to be needful, but

at length the buds would come forth; and then, according to the indication of

the season, the wished-for vessel.

Thus is it with regard to the Church. God has given us a point of hope, and He has

also instructed us with regard to indications of its accomplishment: the point

of hope is that to which the soul tends, while the detail of intervening

circumstances affords the needed instruction, from which is learned the

practical walk of those who possess such a hope. If held in the Spirit, these things cannot

take away from the power of the hope - they were revealed for the directly

contrary purpose: the early Church knew them, and found them to have a

practical and separating power; and in the body of detail with which the

epistles (especially the later ones) are furnished, the dark statements of

coming evil are given in order that the evil may be avoided, and the bright

hope of the glory of the day of Christ might shine through it all and in

contrast to it all. Had not the Church

been so taught, the taunt, “Where is the promise of His

coming?” might indeed be felt as troubling the soul; but when we know

that we have been warned of deeper darkness before the morning, we may indeed

feel that the more conscious we are of deepening gloom, the more rejoicingly may we look onward to the dawn.

Nothing gives us any indication of the immediate introduction

of the latter day, except this to which Christ directs us; we may see many

things to make us expect that the fig-tree would soon bud, but when we see the

buds (and not till then) can we speak with certainty as to what is forthwith to

come to pass. We might see attempts of

the nations to set the Jews in the Holy Land - this ought to make us look

carefully to Jerusalem; God might hinder those efforts, or He might allow the

fearful closing scenes of this dispensation to issue out of them, as at length

He will do.

The importance of the detail of prophecy is very great to the believer: it

certainly is a sad thing to see this extensive portion of God’s truth

overlooked and neglected. It is by the

detail of prophecy that we learn how to walk in the midst of present things

according to God; it is thus we learn His judgment about them, and what their

issue will be. Many Christians directed

their minds much to this a few years ago; but it cannot, I believe, be denied

that this portion of revealed truth has more recently been neglected and

overlooked. Those who have done this

have surely omitted to see how important its present bearing is on the

conscience and conduct: what other portion of revelation shows so clearly the

separateness from all that is opposed to the Lord, to which believers are

called?

There is such a thing as having held truths and then let them

slip; this shows a want of Christian watchfulness. There is such a thing as

having set truths before others, and when the time of their application arrives,

failing in using them ourselves. Most

spiritual minds feel conscious of the power of Satan being great at this time

and his workings peculiarly dangerous; but if I see from the word of God that

these things are to be, I shall be one of those who know these things

beforehand, and this knowledge is to be used as my safeguard, that I be not

carried away with the error of the wicked.

The voyager who knows from his charts those parts of his course in which

danger most exists should be found the most prepared to act in the emergency;

it will not take him by surprise.

But it may be said that if results are rightly known nothing

more is needed; but surely then we should be using our own thoughts as to all

the things connected with those results.

The mere knowledge of a coming deluge would never have led to the

construction and arrangement of the ark.

The knowledge of a result may lead to presumption of the most fearful

kind. The whole testimony of the word is

our safeguard.

The following Remarks on the Prophetic Visions in the Book of

Daniel are intended especially to direct the mind towards some of the important

portions of the detail of prophecy with which the Scripture furnishes us. Should they be found helpful to Christians

who desire to learn from the prophetic word and to know for themselves what

that word teaches, their object will be fully attained. To this end may the Lord vouchsafe His

blessing!

* *

* * *

* *

THE IMAGE (DANIEL 2) [Pages 6-23]

The book of Daniel is that part of Scripture which especially

treats of the power of the world during the time of its committal into the

hands of the Gentiles, whilst the ancient people of God, the children of

Israel, are under chastisement on account of their sin.

The first chapter opens with the statement that

Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon, came up against Jerusalem, that he besieged

the city, that “the Lord gave Jehoiakim,

king of Judah into his hand, with part of the vessels of the house of God,

which he carried into the land of Shinar, to the

house of his god; and he brought the vessels into the treasure-house of his god”. This may, I believe, be regarded as such an

introduction to the book as shall guide our thoughts as to its subject; the

nation of Israel had departed from God, and He now delivers Judah, that portion

of them with whom He had dealt in the most protracted long-suffering, into the

hands of Gentiles, to whom He now commits power over His chosen city,

Jerusalem. The distinctive object in the

book of Daniel is to reveal, at the very period at which this committal has

been made, what would be the course, character, and consummation of the power

so bestowed.

We may divide this book into two portions - that part which is

written in the Chaldee language, and that which is written in Hebrew. While we see that the book has one general

scope - namely, Jerusalem given by God for a time into the power of the

Gentiles who bear rule - we may regard this in two ways; we may either look at

Gentile power in the outline of its history, or we may look at those things

relating to this power in their local connection with Jerusalem. Now, the course, character, and crises of

Gentile power are taken up in this book in the Chaldee language, while those

things which are limited in their application to the Jews and

There are very few portions of the

Scripture which are written in Chaldee; there are some parts of Ezra (chap. 5: 8 to 6: 19,

and 7: 12-27) so written, which bring before

us the children of Israel as being under the power of the Gentiles; there are

some parts of this book; and there one verse in Jeremiah

(10: 11) which contains a message sent to

the Gentiles. This verse occurs just as

the gods of the nations had been mentioned in contrast with the living God.

It is important that we should so bear

in mind the inspiration of Scripture as to recognise that nothing respecting it

can be looked on as accidental; there must be every circumstance a reason as to

whatever God has written, and however He has written it, whether we possess

sufficient spiritual intelligence or not to apprehend it. Now, in such a case as the present we may be

sure that God has not made this difference of language without a very definite

object. The Chaldee portion of Daniel

commences at the fourth verse of the second chapter, and continues to the end

of the seventh chapter: all the rest of the book is written in Hebrew. In the Chaldee portion we see power in the

hands of the Gentile presented before us to its character, course, and

consummation; and in the portion of the book we see the same power localised in

connection with the Jews and

We are often instructed in Scripture by having the same set of

facts presented before us in different aspects: each aspect may show but a few

features of difference, but still enough will be found to evince that the

variety is not without its value. As an

illustration of this we may take the parables of our Lord, in the thirteenth

chapter of St Matthew. He teaches there

on one general subject, the effects which would result from the introduction of

the gospel amongst men: He illustrates the results, both of good and of evil

(from the counter working of Satan), until the day when the tares shall be

separated from among the wheat - when the fishes, good and bad, shall receive

their respective allotments. Instead of

one narrative, or one continuous parable, He uses many, and thus we receive

instruction in its individuality as to its several parts, and also in its

completeness as to the whole instruction given.

This mode of Scripture teaching, by the presentation of many pictures

of the same truths, in order that their bearings and connections may be clearly

and rightly apprehended, is especially found in the book of Daniel; in the

first chapter of which we see Judah, because of sin, delivered into the hands

of their enemies and carried into exile to Babylon.

Thus it is that the prophet is placed in the land of

strangers: Daniel had not personally committed the sins which led to the

captivity, but as part of the Israelitish nation it

was his to share their lot. He and his

companions are brought into a place of particular connection with the king’s

court, and this was an occasion of proving if their hearts were faithful to God

or not. Daniel refused the appointed

portion of the king’s meat, of which he, as an Israelite, could not partake

without defilement, and thus in the midst of

In the second chapter we read of the vision shown by God to

the king of

In the vision of this chapter the moral character and acting

of this power towards God are not stated (except indeed as one who knew the

mind of God might gather it from the crisis), but for this we must look for

further light in the subsequent visions of the book.

Here all is presented as set before the king according to his

ability of apprehension, the external and visible things being shown as man

might regard them. The vision of

Nebuchadnezzar was of a great image with the head of gold, the breast and arms

of silver, the belly and thighs of brass, and the legs of iron; in the

interpretation all these several parts are taken up, and the symbolic meaning

of each is stated. The four metals of

which the image consisted represented four kingdoms which should successively

bear rule in the earth.

To understand

the Scriptures aright we have no occasion to go beyond the limit of the

Scriptures themselves. The same passage of revealed truth which tells us of the

authority of holy Scripture tells us also of its sufficiency: “All Scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is

profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in

righteousness; that the man of God may be perfect, thoroughly furnished unto

all good works” (2 Tim. 3: 16, 17). Thus nothing can be needed by the man of God, in order that he

should be “thoroughly furnished”, beyond the

inspired writings contained in the Bible.

We have then no necessity to go out of the Scripture itself in order to

gain information as to those things of which we read in Scripture; we may find

many things which are interesting as bearing upon Scripture, but still whatever

God looks on as needful for the establishment of the souls of His people, and

for their spiritual intelligence in His truth, is to be found within the limits

of His Scripture. History is not

revelation; and we are nowhere commanded to search history to learn the truths

found in God’s word; although it may be owned most freely that God’s word sheds

a light upon the things which man has written as history, and that many lessons

may be learned from seeing how different are the thoughts of God and of man

about the same events.

We have no occasion whatever to go beyond the limits of

Scripture to learn what the four kingdoms are which are thus mentioned in

Daniel.

First. It was said expressly to

Nebuchadnezzar that the head of gold symbolised his kingdom (ver. 37, 38): “Thou, 0 king,

art a king of kings: for the God of heaven hath given thee a kingdom, power,

and strength, and glory: and wheresoever the children of men dwell, the beasts

of the field and the fowls of the heaven hath he given into thine hand, and

hath made thee ruler over them all. Thou

art this head of gold.” These

last words fix the first kingdom incontestably to be that of

Now, as to the terms in which the extent of Nebuchadnezzar’s

power is stated, of course we are not to

understand that he actually held and exercised this rule over every part of the

inhabited earth, but rather that, so far as God was concerned, all was given

into his hand, so that he was not limited as to the power which he might obtain

in whatever direction he might turn himself as conqueror; the only earthly

bound to his empire was his own ambition.

This is just what we find also in Jer. 67: 5, 6:

“Thus saith the Lord of hosts. ... I have made

the earth, the man and the beast that are upon the ground, by my great power

and by my outstretched arm, and have given it unto whom

it seemed meet unto me. And now have I

given all these lands into the hand of Nebuchadnezzar the king of

[* The extent of Nebuchadnezzar’s

dominion was, however, very great, far greater than many have supposed. In the

course of his conquests he must have become the wielder of most of the powers

of the earth, as it then was. We know

something of the greatness which

Second. He was told, “after thee shall

rise another kingdom inferior to thee”.

To find out what kingdom was intended we have only to inquire what

kingdom succeeded to that of Babylon; in 2 Chron. 36: 20 we read of Nebuchadnezzar, “them that had escaped from the sword, carried he away to

Babylon, where they were servants to him and his sons until the reign of the

kingdom of Persia”. And indeed in

this book of Daniel itself we find a plain intimation of what the second

kingdom should be which should succeed that of Babylon; in chap. 5: 28 it is said, “Peres;

thy kingdom is divided, and given to the Medes and Persians.” Although these were two nations, yet the

Medo-Persian kingdom is regarded as being one, as we also find in chap. 8: 20.

Third. In the vision the king had seen “his belly and his thighs of brass” (verse 32), and this is defined in the

interpretation to be “another third kingdom of brass,

which shall bear rule over all the earth”. In chap. 8

we learn (verse 21) what this kingdom was,

to which dominion was given after that of the Medes and Persians – “the rough goat is the king of Grecia”; this symbolic

goat had been previously spoken of as destroying the ram, which was used in

that vision as the symbol of the Medo-Persian kingdom. The commencement of chap.

11. tells us the same thing.

Fourth.

In the vision

the image had been seen with “his legs of iron”

(verse 33); in the interpretation we read, “the fourth kingdom shall be strong as iron, forasmuch as iron

breaketh in pieces and subdueth all things, and as iron that breaketh all

these, shall it break in pieces and bruise” (verse

40). We shall not find the name of this fourth kingdom in the Old

Testament, although we see here, and in other places, its character and

description. But we learn from the New

Testament what this kingdom is; for we there find another bearing rule over the

earth after that of

Thus we may see that it is wholly needless to go to any other

source than that of the Revelation of God in order to discover what these four successive

kingdoms are - the Babylonian, Medo-Persian, Grecian, Roman.

It must be obvious to the Christian student of Scripture how

much more satisfactory it is thus to learn the details of facts from the word

of God than from the records of history; the

latter may be true, but the former commands our faith, and leaves us with a

confidence of certainty which we never can have with regard to facts derived

from other sources. It would have

been indeed strange if it had been necessary for us to draw from the doubtful

statements of profane historians in order to understand prophecy; and we must

also remember how many would find it impossible to do this.

The metals which symbolise these kingdoms become less and less

pure. A certain process of deterioration

appears to be marked out as to power, while passing from one kingdom to

another.*

[* It may be worthy of observation

that the metals in the image lessen in their specific gravity as they go

downwards; iron is not so heavy as brass, and thus the weight is so arranged as

to exhibit the reverse of stability, even before we reach the mixture of clay

and iron.]

When Nebuchadnezzar received the committal from God it was

simply power from Himself, not derived from man, not dependent on the will of

others, but put by God into his hand and exercised in responsibility to Him

alone, as the only ruler of princes.

Nebuchadnezzar might rightly bear, as far as man was concerned, the name

of autocrat: his will was law. Now, we

can see in part from Scripture how power deteriorated in its character in the

other kingdoms. The

In

the continual hindrances thrown in the way of the Jews after their return from

Babylon, when they attempted to carry out the edicts of the Persian kings in

their favour, we see manifest proof how the governors, and others in authority

under the Persian kings, could oppose the execution of the pleasure of the

sovereign.

We do not read much in Scripture as to

the Grecian power, and therefore details as to the manner of the deterioration are not to be pressed; only

the fact of such deterioration of

power being intimated should be noticed.

In one respect the Scripture appears

to indicate the mode of this deterioration, when it tells us of the divisions

of the third kingdom, so that it continued in a fragmentary and not a united

form.

The fourth kingdom is said to be “as

strong as iron”. As a metal this

is in many respects inferior to brass, although possessed of much more strength

for certain purposes, and capable of far more extensive application. Strength

and force are spoken of, but still apparently deterioration.

It may also be noticed that the deterioration of the fourth

kingdom is especially shown in its last state.

Each of the four kingdoms appears as succeeding that which had

gone before, not as annihilating it, but as incorporating it with itself - each

making, as it were, the dominion of the metal which had gone before a part of

itself, just so do we read in chap. 5: 28 of

the manner in which the kingdom of the Medes and Persians succeeded to that of

Babylon: “Thy kingdom is divided and given to the Medes

and Persians”; the kingdom not being, as it were, destroyed, but

transferred - that is, the cities and nations were to continue in existence,

while the glory which had belonged to them passed into the hand of other

powers.

[* The senate often made a show of

appointing the emperor, but their decree was, in general, simply a needful

compliance on their part. So, too, in the case of Vespasian, although the

people of Rome professed to bestow on him the imperial power (as recorded in

the still existing bronze tablets), yet, in fact, they had no real power, for

Vespasian already had the military rule in his own hands.]

The committal of power in all the fullness spoken of in verses 37, 38 appears to belong to Nebuchadnezzar

personally, or at all events to have been confined to the

In verse 40 we have rather

the character of the Roman power than its territorial extent; this latter

subject does not appear to belong to the scope of the present vision, which we

have to regard especially as speaking of these kingdoms in their succession

from

The “potter’s clay” (verse 41) means, I believe, simply “earthenware” - that which is hard but yet brittle;

softness does not seem to be at all the thing pointed out. Now, an image which stood partly upon feet of

earthenware would be very stable so long as there was nothing but direct

pressure brought to bear upon these feet, while a blow falling upon them would

break them to pieces, and that only the more thoroughly from the fact of iron

being intermixed with the earthenware; this I believe to be the thought here

presented to us.

We see from verse 42 that

the part of the feet thus formed of iron and clay intermixed was the toes; and

the interpretation which is given is, “the kingdom shall

be partly strong and partly broken” (or, rather, “brittle”). In verse 43 the explanation is continued, “they shall mingle themselves with the seed of men”;

thus there will be power (in its deteriorated form, iron) mixed up with that

which is wholly of man, and which, when put to the proof, is found to be only

weakness itself.

Thus we see this fourth empire especially brought before us at

a time when in a divided condition, and when thus debased. The number of the toes of the feet appears to

imply a tenfold division: this may be taken as a hint given to us here,

although the more specific statement of the fact is not told us till farther on

in this book. This kingdom is then divided into parts, which we shall see from

other portions of the Scripture (especially chap. 7)

to be exactly ten. Power in the hands of

the people is seen, having no internal stability, although something is still

left of the strength of the iron.

Verse 44. Here we see that when

the image is fully developed, even to the toes of the feet, then destruction

falls on it. In the vision it had been

stated (verse 35) that all the materials of

the image became, when smitten, “like the chaff of the

summer threshing-floors, and the wind carried them away, that no place was found

for them”. This expression may

give us some intimation of the moral character of these kingdoms before God,

such as we do not find anywhere else in the chapter; just as we read in the

first Psalm, “The ungodly ... are like the chaff which the wind driveth away.”

The expression in verse 44,

“in the days of these kings”, is worthy of attention, for it brings before

our minds more than had been expressly stated, either in the vision or in the

interpretation; namely, that the kingdom which had last borne rule has been

divided, and that the toes of the feet do actually symbolise such divided

parts. “These

kings” cannot mean the four successional monarchies, because in that

case the plural number could not be used seeing that they do not co-exist as

the holders of power. The fourth kingdom

is divided into parts (which other Scriptures show to be exactly ten), and “in the days of these kings shall the God of heaven set up a

kingdom which shall never be destroyed”.

This kingdom is in its character utterly unlike the four which

had preceded it; it has nothing springing from Babylonian headship, which may

be transferred, and become deteriorated in the hands of men, but it stands in

direct contrast to all that has been.

It is important to observe very distinctly what is the crisis

of the image: “a stone was cut out without hands, which

smote the image upon his feet that were of iron and clay, and brake them to

pieces. Then was the iron, the clay, the brass, the silver, and the gold,

broken to pieces together, and

became like the chaff of the summer threshing-floors; and the wind carried them

away, that no place was found for them: and the stone that smote the mage became a great mountain, and filled the

whole earth” (ver. 34, 35).

Now, what does the stone so falling upon the feet of the image

symbolise? It has been sometimes thought

that it alludes to grace, or to the spread of the gospel; but surely if the

very words of the Scripture be followed, we shall see that destroying judgment on Gentile power is here spoken of, and not any gradual diffusion of the knowledge

of grace. The image is standing on

its feet, part of iron and part of earthenware; the stone then falls from above

upon these feet, and the whole image is destroyed as it were with one crash.

Now, our Lord speaks of

Himself as the “stone”, and makes reference, or direct citation

of, several passages in the Old Testament in which he had been so

designated. Thus in Matt. 21 He says, “Did ye

never read in the scriptures, The stone which the builders rejected, the same

is become the head of the corner: this is the Lord’s doing, and it is

marvellous in our eyes? ... And whosoever shall fall on this stone shall be broken; but

on whomsoever it shall fall, it will grind him to powder” (ver. 42, 44).

Our Lord here cites from Psalm 118,

and alludes to the mention made in Isaiah 8

to the stone on which Israel has stumbled and been broken; and he likewise

clearly refers to the destroying judgment which takes place when the stone, now

exalted at the head of the corner, falls thus upon the fabric of Gentile power

– “it will grind him to powder”.

“The stone” must be taken as a definite appellation of

our Lord. We see this from Psalm 118: 22, Isaiah

8: 14 and 28: 16, Acts 4: 11, and 1 Peter

2: 4, 6, in all of which Christ is spoken of under this name. Now, this

cannot refer to Him as born into the world, because the fourth kingdom was not

then in its divided condition - no toes were then in existence. This falling on the feet of the image could

not, therefore, have anything to do with our Lord when He was upon earth. Equally impossible is it for this to

symbolise the spread of the gospel; for,

so far from Christians being put in the place of destroying those that bear

earthly rule, they are taught submission to the powers that be as ordained

of God, and their place is to suffer, if needs be, but not to rebel.

Thus,

it is clear that the Lord Jesus is here referred to as coming again - in the day when He shall take to Himself

his great power and shall reign - when He shall be revealed “in flaming fire, taking vengeance on them that know not God,

and obey not the gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ” (2 Thess. 1: 8).

It might occur as a difficulty that the Roman empire does not

exist as one united body; and hence it might be thought that the stone falling

on the image must have been some past event: but observe, the

[* Not only did the monarchies of Western Europe spring up, as

each holding a portion of Roman sovereignty, but also in their continued

administration this fact has been habitually recognised. Each has regarded as holding a portion of Roman imperium. See Note on the

Now, we may regard “the stone”

in three different ways, for we find it in Scripture so spoken of, in

connection with

I have already spoken of the relation of this stone to Gentile

power, but I would remark further, that the utter distinctness of this power

from that which stands in grace is most vividly presented to us in the crisis

of this power. The Church is built upon

the stone; the image is destroyed by the stone falling upon it. We ought carefully to note the distinctions

which God makes in His word, and no line of demarcation which He has laid down

is more plain than that which exists between the world and its power on the one

hand and the Church on the other. How

wondrously does it show the power of Satan in confusing the mind as to things

that differ, that it should have been

supposed to be possible for the

Church rightly to rest upon the power of this world upon that which the Lord

Jesus is going thus to judge!

Let the saints rightly value their place as identified with

Christ, as resting upon Him, and

then they will see aright how to act as to any connection with the world and

its power. A saint who identified himself with the image would be, as it were, so

far seeking to put himself in the place of that which will receive destroying

judgement. It is quite true that God

will keep from final condemnation every soul that He has quickened by the

Spirit to believe in Christ; but it would evince a hardihood of mind which

seems scarcely compatible with grace for any one deliberately to say, “God will keep me, and so I may put myself in the place where

judgment will fall.” It is for us

to have nothing to do with that upon which the judgment of God will fall, but to realise our union with Him who will

execute the judgment, and in whose coming kingdom his people will share.

The second chapter of Daniel may be looked on as the alphabet

of the prophetic statements contained in the book; and it is well for the mind

to be grounded in the truths contained in this portion of the book, before

other parts of it are searched into. We

have here the four successive empires, the last of these in a divided and

deteriorated condition and then, in contrast to the whole that had preceded, a

kingdom, which shall last for ever, set up by the God of heaven - the coming of

the Lord Jesus in destroying judgment being the turning point which changes the

whole scene; all that had failed in the hand of man then passing away, and that

which is kept in the Lord’s own hand being then introduced.

If we refer to the 8th

Psalm, we shall see the extent of Christ’s dominion spoken of in terms

very similar to those which in this chapter had been used to describe the power

committed to Nebuchadnezzar: we thus see how the power of the earth, entrusted

to him, and which failed in his hand, is taken up by Christ, as One who really

is able to hold and to exercise aright this dominion in all its wide extent.

* *

* * *

* *

THE GREAT TREE (DANIEL 4) [Pages 24-29]

The Vision in this chapter does not particularly connect itself

with the object proposed in these “Remarks”, which was to speak of those

portions of Daniel which are still, in a great measure, future; it is, however,

one of much interest, for here we find, in the past accomplishment of a vision,

an earnest of the exact and precise fulfilment which all these visions must

necessarily receive.

The form of this chapter is remarkable;

it is a decree proceeding from Nebuchadnezzar himself, after those things had

passed over him which God foretold to him in vision; when he was forced to

confess “the signs and wonders that the high God hath

wrought towards me. How great are his

signs! and how mighty are his wonders! his kingdom is an everlasting kingdom,

and his dominion is from generation to generation” (ver. 2, 3). Thus did the king, at length, acknowledge the

hand and power of God. After the vision

in the second chapter had been declared to him by Daniel, he looked to the

prophet as though he were the source of the communication of

divine truth to him: “then the king Nebuchadnezzar fell

upon his face, and worshipped Daniel, and commanded that they should offer an

oblation and sweet odours unto him” (2: 46);

he then acknowledged God as the revealer of secrets, although it is evident

that his heart was in no way humbled before Him.

And thus, in the next chapter, so far from honouring the

living and true God, the king set up his golden image in the plain of Dura,

commanding that all should worship the idol; as if he, who was himself the

receiver of power from God, could himself possess authority to decree anything

as to who should or should

not be the object of religious worship.

The miraculous deliverance of those who refused to obey the king’s

command to commit idolatry leads to an acknowledgment, on his part, of the God

whose power had thus shown itself; so that he made an edict that no one should

speak against the God of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, on pain of death.

But still his heart was lifted up in pride; he continued to trust

in his own power; and this fourth chapter is his own remarkable declaration how God had dealt with him to humble his

haughty spirit.

After acknowledging the power of God, he goes on to say, “I Nebuchadnezzar was at rest in mine house, and flourishing

in my palace; I saw a dream which made me afraid, and the thoughts upon my bed

and the visions of my head troubled me.”

He then describes (ver. 6, 9) how he sought in vain, from the wise men

of

Having thus narrated the dream, the king sought the

interpretation from the prophet. Daniel

shows us that the communication of truth from God, or a place of special

service to Him, does not at all interfere with the full action of right human

feelings. He saw that the vision

foretold a solemn chastisement from God which should fall upon Nebuchadnezzar,

and therefore he felt deeply his own position as being thus the communicator of

evil tidings. “Then

Daniel, whose name was Belteshazzar, was astonied one

hour, and his thoughts troubled him. The

king spake and said, Belteshazzar, let not the dream, or the interpretation

thereof, trouble thee. Belteshazzar answered and said, My lord, the dream be to

them that hate thee, and the interpretation thereof to thine enemies.” He then, after describing the tree in all its

greatness, adds: “It is thou, 0 king, that art grown

and become strong: for thy greatness is grown, and reacheth unto heaven, and

thy dominion to the end of the earth.” He then applies the Judgment on

the tree to the king: “They shall drive thee from men,

and thy dwelling shall be with the beasts of the field, and they shall make

thee to eat grass as oxen, and they shall wet thee with the dew of heaven, and

seven times shall pass over thee, till thou know that the Most High ruleth in

the kingdom of men, and giveth it to whomsoever he will.” But still the king was told that his kingdom

should be sure unto him, after he knew that the heavens do rule. Daniel’s feeling towards the king did not

allow him to rest with merely delivering the prophecy of chastening; he exhorts

the king as having a true and earnest desire for his welfare: “Wherefore, 0 king, let my counsel be acceptable unto thee,

and break off thy sins by righteousness, and thine iniquities by showing mercy

to the poor; if it may be a lengthening of thy tranquillity.”

A year passed on: the king’s heart was not humbled; he still

looked on his power and might as his own, and did not confess that rule and

authority are from above, and not from beneath.

He was walking in the palace of the

[* It was reserved to our day to bring

out to light an abiding record of the extent of the works of Nebuchadnezzar:

the inscription in the arrow-headed character, found on the bricks in every part of the plain of Babylon, is “Nebuchadnezzar, the son of Nabopolassar”. Turned to so many new uses, they still

speak of the establisher of

The appointed seven years were at length accomplished in the

king’s humiliation, and then (he says), “At the end of the days I

Nebuchadnezzar lifted up mine eyes unto heaven, and mine understanding returned

unto me; and I blessed the most High; and I praised and honoured him that

liveth for ever”, etc. (ver. 34). And

then, according to the word of the Lord by Daniel, his kingdom was restored to

him, and “excellent majesty was added to him.” He whose earthly power had been so great had

now learned to “praise, and extol, and honour the King

of heaven, all whose works are truth, and his ways judgment: and those that walk in pride, he is able to

abase”.

This is an instructive lesson of the exactitude with which prophecy

is accomplished: it may teach us how we

should expect the fulfilment of what is yet future. These things took place under the head of the

first of the four great monarchies, and thus they might have been regarded as a

warning to those possessed of the power of the earth, that they might learn who

gives them their power, and who it is that ruleth among the children of men.

How little this was heeded is shown us in the next chapter,

where Belshazzar, unmindful of what he had known (chap. 5: 22) of the actings of

God, went on in a course of un-humbled blasphemy. The neglected warning made the condemnation

all the greater. The

Thus has God, from the beginning, shown us what the result is

of power in the hands of the Gentile monarchs: the Giver of authority has been

continually forgotten; it has been regarded as something not received, or else

it has been attributed to wrong sources.

In the sixth chapter of Daniel we find one remarkable

exemplification of what man may do when possessed of authority: Darius was led

by the craft of the presidents and princes to decree that no petition should be

asked for thirty days of any God or man save of himself only. He seems to have thus unwittingly put himself

in the place of God, and thus became an aider of the evil design formed against

Daniel - a design which, by the miraculous interposition of God, issued in the

destruction of those that formed it.

All the results set before us in this book show that power will never be held as from God, and

for God, until Christ takes it into his own hand. God dealt with the first head of Gentile

power for the instruction of those who should come after (“to the intent that the living may know that the Most High

ruleth in the kingdom of men”); but the result has only been farther and

yet farther estrangement from God, until this shall be fully exhibited in the

last head of Gentile power.

*

* * *

* * *

THE FOUR BEASTS (DANIEL 7) [Pages

30-50]

This chapter contains a prophetic vision, and its interpretation

given to the prophet, in which the objects are presented not merely according

to their external aspect (as had been the case in the second chapter, in the

vision seen by the king), but according to the mind of God concerning them.

In this vision we not only have again four successive kingdoms

upon earth, and an everlasting kingdom set up by God on the destruction of the

last of these, but we find also distinct details as to moral features, as

regards God and those who belong to Him.

This vision was seen in the first year of King Belshazzar,

when the power of

In speaking of the origin of these four kingdoms we read (verse 2.) of “the great

sea” as the scene from which the four symbolic beasts arise; this is

not, I believe, an expression which we should overlook, for the “great sea” is always used in every other passage of Scripture

in which the phrase occurs as meaning distinctively the Mediterranean Sea. This, I believe, presents that sea before us

as the centre territorially of the scene of this vision.

Four beasts arise out of this sea (verse

3), and these are (verse 17)

interpreted to be “four kings which shall arise out of the earth”. From the words of verse

23, “The fourth beast shall be the fourth kingdom

upon earth”, it is clear that the words “king”

and “kingdom” are used, in passages of this

kind, almost in an interchangeable sense - a kingdom is sometimes looked at as

headed up in its sovereign, whose name is used; at other times the name of the

kingdom is used in speaking of the power, designs, etc., of the sovereign. This must be borne in mind just as much in

reading prophetic narrations as in the common language of life.

We may thus, interchangeably, speak of the Babylonian,

Medo-Persian, Grecian, and Roman empires, or of those of Nebuchadnezzar, Cyrus,

Alexander, and Augustus.

The distinct scriptural proof of what these four kingdoms thus

succeeding each other must be has been given in Remarks on the Great Image, chap. 2, pp. 12. 15: it is needless to repeat it

here; but it may not be amiss to add that the four individuals regarded by God

as the heads of these several monarchies are all of them definitely brought

before us in Scripture, either in historical account or else in distinct

prophecy as to their persons, or both.

Of the four personal heads, Alexander alone is not a subject of

Scripture history, as well as of prophecy.

Now while I believe it to be most important for us to remember

that, for the real spiritual understanding of the word of God, and for its use

as bearing on our consciences, we need no knowledge but that which the Spirit

has given us in the word, yet we may often find truths intimated in the

prophetic Scripture, which throw much light upon what we learn as facts from

other sources. This is a very different

thing from using history in a manner for which God has given us no warrant, as though

the world could be illuminated by any such doubtful, defective, and glimmering

light of man’s kindling.

Now, in looking at “the great sea”

as the territorial scene of the vision, we must also remember that the time to

which the visions in Daniel belong is that of Gentile power ruling over

Jerusalem and the Jews, and also that the powers are defined (verse 17) to be monarchies; we thus find that each

of these beasts symbolises a monarchy bordering on the Mediterranean and having

This, as it appears to me, is what we have presented before us

in the territorial allotment of the sphere of this vision.

The brief interpretation of the vision is given in verses 17, 18: “These

great beasts, which are four, are four kings, which shall arise out of the

earth: but the saints of the most high [places] shall

take the kingdom, and possess the kingdom for ever, even for ever and ever.” This gives us the general outline of the

truths here taught us - the succession of the monarchies, and a kingdom which

should arise in contrast to the earthly empires.

The first of these four kingdoms is here symbolised by a lion (verse 4) with eagles’ wings: the prophet beheld it

until the wings were plucked - until (I suppose) its ability for widespread

conquest had passed away; it was made to stand on its feet as a man, and a

man’s heart was given unto it. These words

seem to me an intimation of what had taken place with regard to Nebuchadnezzar,

who was taught by the remarkable discipline of God that the Most High ruleth in

the kingdom of men.

The second monarchy was symbolised by a bear: this beast made

for itself “one dominion” (for so I believe we

should render the expression which stands in our version “one side”). The

Medes were an ancient people, and the Persians were a comparatively

modern tribe; neither of these could be looked on as likely to overturn the

power of Babylon; but by the expression “one dominion”

there seems to be a hint of the second kingdom being a united power, so that the one dominion should

be a combination, and thus it stands in contrast to the third and fourth

monarchies which were at first united and afterwards were divided. The three ribs seen in the mouth of the bear

seem to indicate the conquests which it was devouring, according to what was

said to it, “Arise, devour much flesh.”

The four-headed winged leopard, which symbolised the third

kingdom, seems to indicate the rapidity of the conquests of that power, and the

fourfold division which was its after condition.

But it is impossible to read this vision without seeing that

the fourth kingdom is the principal topic brought before us, and that the other

three simply appear as introductory. We

see from verse 19 that this was the

impression made upon Daniel’s mind by that which was exhibited to him in

symbol. But not only was the fourth

beast the most conspicuous object, but it was while in a certain condition that

the details concerning it are given, we look in fact rather at the crisis than

the course of its history. The

description of the beast is given in verse 7:

“After this I saw in the night visions, and, behold, a

fourth beast, dreadful and terrible, and strong exceedingly; and it had great

iron teeth: it devoured and brake in pieces, and stamped the residue with the

feet of it: and it was diverse from all the beasts that were before it”;

this is the general description, and then there is added, “and it had ten horns,” and then another horn is spoken

of as springing up amongst the former ten. Now, it is clear that it is the

actings of the beast when possessed of this horn, or rather perhaps of this

horn as concentrating the power of the beast, with which in this vision we have

to do.

In the statement which was made to

Daniel we find a very distinct explanation of these things: it was said to him

(verse 23), “The

fourth beast shall be the fourth kingdom upon earth, which shall be diverse

from all kingdoms, and shall devour the whole earth, and tread it down, and

break it in pieces: and the ten horns out of this kingdom are ten kings that

shall arise.” Thus we see that

the horns symbolise what this kingdom would become at a particular point of

time, namely, when that empire, which was once united as a monarchy under the

power of the Caesars, should be divided into ten kingdoms. An intimation of this had been given in the

number of the toes of the image in chap. 2,

and the same thing is found both in symbol and in direct statement in the book

of Revelation (see, for instance, chap. 13: 1,

and 17: 12).

This, then, must be the state of the Roman earth at the time

when another king, whose actings are here detailed, arises in the midst of the

other kings.

This king is at first symbolised by “a

little horn”: this is not his

designation when acting in blasphemy and persecution, for then the symbolic

horn had become very great, “his look was more stout

than his fellows”; but at first he rises like “a

little horn” in the midst of the other

horns, and then so increases in power as far to surpass them all.

The rise of this last horn was thus shown in the symbol: “I considered the horns, and, behold, there came up among them

another little horn, before whom there were three of the first horns plucked up

by the roots: and, behold, in this horn were eyes like the eyes of man, and a

mouth speaking great things” (verse 8). This

is explained, in verse 24, to be another

king rising after the first ten, “and he shall be

diverse from the first, and he shall subdue three kings”: and then his

persecution and blasphemy are mentioned.

As spoken of at first, we meet with nothing but his blasphemy

against God, and then (verse 11) judgment

from God falling upon the beast because of this blasphemy; but when Daniel is

making inquiry as to what all this might mean, some further particulars are

brought before us: “I beheld, and the same horn made war with the saints, and prevailed against them;

until the Ancient of Days came [as had been shown in the previous

vision, ver. 9], and judgment was

given to the saints of the most high [places]; and

the time came that the saints possessed the kingdom” (verses 21, 22).

This is explained (verse 25), “And he shall speak great words against the Most High, and shall wear out the saints of the

most high [places], and think to change times

and laws: and they shall be given into his hand, until a time and times and the

dividing of time.”

Thus, we see this king using his power in a twofold form of

opposition to God - in open and direct blasphemy against Him, and in the persecution of his saints. We also find that this opposition continues

to the end of his reign, and that this is consummated by the direct judgment of

God.

While the scene presented on earth is the beast energised by

this last horn, wearing out the saints and blaspheming the name of God, we have

also the veil so withdrawn as to unfold to us what at the same time takes place

in heaven. In verses

9 and 10 we have this displayed to

us; a court of judicature is set in heaven, where God judges, and, in

consequence of His judgment, the sentence which is pronounced above, unseen by

any eye save that of faith, is executed upon the earth. “I beheld till the

thrones were cast down [or rather were set], and

the Ancient of Days did sit, whose garment was white as snow, and the hair of

his head like the pure wool: his throne was like the fiery flame, and his

wheels as burning fire; ... the judgment was set, and the books were opened”; and

then the effect on earth of the judgment in heaven is thus spoken of. “I beheld then

because a cloud received him out of their sight”: to instance one of

these places:- when our Lord stood before the high priest, He said, “Hereafter shall ye see the Son of man sitting on the right

hand of power, and coming in the clouds of heaven” (Matt. 26: 64).

Now, in the expression “sitting on the right

hand of power” He clearly referred to Psalm

110: 1 (see also Psalm 80: 17), but in speaking of the clouds of heaven

He as manifestly alluded to this place in Daniel: the one passage of the Old

Testament brings before us the place into which He, who has thus been rejected

by men, is received by God; the other brings before us the glory which shall be

manifested in His coming and taking the rule into His own hands.

But there is this difference between the mention made of “the clouds of heaven” in Daniel from that in the New

Testament, that here we have not the coming forth of Christ spoken of, but that

which immediately precedes it; I say advisedly immediately precedes, because He sits at the right hand of

Jehovah until His enemies are

made His footstool, and when God has accomplished that, then this kingdom is

given in actual investiture to the Son, and He comes forth to crush His so

prepared footstool beneath his feet.

But though this scene, in which the clouds of heaven are

mentioned, is not identical with the actual coming forth of Christ, yet even this passage might

be taken as intimating the very close connection between the two things - for the court of judicature set in heaven

is, so to speak, the intermediate point between His seat in glory, where He now

is, and the manifestation of His person, when “every

eye shall see him”; He has with Him the same adjuncts that He will have

when He returns to this earth.

We have then as the parties before us in the crisis of this

chapter‑

Upon earth: 1. The last horn of the fourth beast, persecuting

the saints and blaspheming God.

2. The beast itself with ten horns (three plucked up before

the last horn), so connected with the horn of blasphemy that it is involved in

the judgment on that horn and is in several important senses responsible for

its acts.

3. The saints worn out and warred against by the horn of

blasphemy.

In heaven: 1. The Ancient of Days taking the place of

judicature and condemning the fourth beast because of the words spoken by the

horn.

2. The Son of Man brought before Him with adjuncts of heavenly

glory, and receiving above a kingdom which He will exercise in government upon

earth.

If we learn simply from Scripture, I think that there can be

no question as to who or what the fourth beast symbolises - that has been

considered already - but with regard to the horn of blasphemy, it is very

important for us distinctly to see from the word of God whether this be a power

past, present, or future. One thing is

clear, that his dominion and actings in blasphemy and persecution continue up

to the coming of the Lord, because it is then the saints take the kingdom and

not before, and till they take the kingdom he wears them out.

Thus, if he be a power whose rise is

past, he must also be present, and some of his actings must be future. And, further, if his wearing out of the

saints has begun, it must also be now going on and must still continue until

the judgment of verse 10. It might also be left to the consciences of

Christians to say whether they are now at this time enduring active

persecutions of this kind, or whether

they are in most places permitted to dwell in external rest and tranquillity.

We cannot, then, possibly speak of this horn of blasphemy as

already past; just as manifest is it that his dominion is entirely future. The considerations just stated appear to

prove this point.

But, further, it is said (verse 25),

“And he shall speak great words against the most High,

and shall wear out the saints of the most High [places], and think to change times and laws: and they shall be given

into his hand, until a time and times and the dividing of time.” Here then we have a chronological statement,

to which we shall do well to take heed.

It is true that this is a period reckoned backward, and thus we can form

no calculation of our own upon it as to times or seasons, but for the purpose

for which God has revealed it, it is so stated as fully to meet the object; it

is a period which runs on to the coming of the Lord Jesus, and must be reckoned

backward from that time. This then gives

the limit of the distinct actings of this horn in blasphemy and persecution; it

commences at the beginning of the “time, times, and a

half”, and runs on to the coming of Christ without any intermission.

This period has been commonly taken (and I have no doubt

rightly so) as signifying three years and a half. Now, we know that it must

mean a period exactly defined, and not about such or such a time; for had

it been merely an indefinite statement, the mention of “half a time” would be useless.

It is impossible to be definite and indefinite at one and the same

time. The word rendered “time” is that which denotes either a stated period or

else a set feast, or else an idea blended, as it were, of the two, namely, the

interval from one of the great set feasts to its recurrence, i.e. a year; thus

then we find a time, i.e. one year; times (the smallest plural, as the

statement is definite), two years,

and half a year, i.e. three years and a half.

The word “time” is similarly

used in chap. 4, where it was foretold to

Nebuchadnezzar that he should be driven from men until “seven times” should

pass over him, i.e. seven years; also in Lev. 23,

where the feasts are mentioned, the Hebrew word which corresponds to the

Chaldee word here used (and which itself is found in chap.

12: 7) is employed in the sense of denoting a set feast, or the period

from one recurrence to another.

Thus then the period at which the especial blasphemy and

persecutions of this horn begin is three years and a half before the coming of

the Lord Jesus - a short time, during which evil will be allowed greatly to

prevail, but then in consequence of its full development the judgment of God

will come in.

This then is briefly his history as given in this vision. The Roman earth is found divided into ten

kingdoms: another king arises who destroys three of the former kings: for three

years and a half he acts in open defiance of God, and in persecution of his

saints: the whole Roman earth is so connected with his deeds as to share in the

judgment which comes from the hand of God upon him, and this occurs at the very

time when the kingdom is given into the hand of the Son of Man, and when the

saints take it with Him.

But many may object, Is not the horn here spoken of the

Papacy? Does not history warrant us in

charging these blasphemies and persecutions upon that power?

To this I reply, No appeal to history can be of any avail in

opposition to direct testimony in the word of God. Thus, unless this power be

wearing out the saints continuously up to the coming of the Lord, the chief

point in supposed resemblance is lost.

And even further, if any one chooses openly and fairly to appeal to

history, he will find discrepancies at every point - for instance, the tenfold

division of the Roman earth of which mention is here made has never yet taken

place, and therefore, of course, the horn which was to arise after the others

has not yet come into existence. It is

quite true that many have given lists of kingdoms which arose in the fifth and sixth

centuries out of the broken parts of the Roman empire, but these have all been

sought merely in the west, as though the eastern half were not to be

considered, when in fact the existence of the eastern empire was protracted for

a thousand years after that period.* And

further, whatever lists have been made out of ten kingdoms, they have all

varied widely both as to the kingdoms themselves and also as to which were the

three which the Papacy overcame. It has

also been entirely forgotten that the Papacy existed before the breaking up of even the western

empire, instead of being a horn springing up after the other ten.

[* Till May 29, 1453, when the Turks took Constantinople and

the last

But it has been said that this horn must be a power existing

through a long period of time, and not a single king; because it is alleged

that in prophetic language a day is used as a symbol of a year, and therefore a

year as that of three hundred and sixty days (twelve months of thirty days

each), and thus the whole time of the persecution of this horn is twelve

hundred and sixty years. This question

is one into which, in its full statement, I cannot enter in this place, but the

reader will find it examined elsewhere more fully.* I will only here remark,

that if this canon of interpretation were sound the period of Nebuchadnezzar’s

madness (“seven times”) would be still

continuing; and not only should we be left in utter uncertainty in every

prophecy in which time was mentioned, but in some we should even find

inextricable incongruities and contradictions. What, for instance, could we

make of the three days during which our Lord was to lie in the grave? But the comparison of the “seven times” which should pass over Nebuchadnezzar is

sufficient in this place: the dominion of this horn is half of that time, both