WILLIAM TINDALE

THE BIBLE TRANSLATOR

AND CHRISTIAN MARTYR.

EDITOR’S FOREWORD.

Important messages are often translated into

many languages to make sure that they can be understood by as many people as

possible. The Bible, which is the Word of

God, contains an important message.

Although recorded long ago, the truths found in the Bible “were written for our instruction” (Rom. 15: 4), to provide us with the knowledge of eternal

salvation through faith in our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ; and with the “hope” of ‘aionian’ (age-lasting) life (Titus 1: 2) to “inherit”

the “kingdom of God,” in the “Age” to

come, (Gal. 5: 21; Eph.

5: 5; Luke 20: 35; Rev. 3: 21; 20: 4,

&c.)

It stands to reason then, that the inspired Word

of God which was written initially in both the Hebrew and Greek languages, should be made available in many other

languages.

Throughout history, God has inspired men to

translate the Holy Scriptures into many languages; but, in Tindale’s day not

everyone relished the idea!*

Pope Gregory XI issued five edicts

condemning Wycliffe, but the

Translator replied: “Englishmen learn Christ’s law best in English. Moses heard God’s law in his own tongue, so

did Christ’s apostles.”

Wycliffe had translated from the Latin Vulgate and mainly copied

the Scriptures and numberless copies of Wycliff’s translation of the Bible were

made and widely circulated, and handed down.

[*NOTE. In some respects, conditions within

Christendom today are similar to those existing in Tindale’s day. Today we have bigoted and ignorant Bible

teachers, indoctrinated with what they have heard and been taught by man’s

wisdom in Bible colleges. Some of these

people, armed with worldly qualifications and false interpretations in

order to appear faithful to their various denominational parties, Bible

schools, and sects, are wilfully neglecting and avoiding the

exposition of certain texts (as those shown above); and are misleading God’s

redeemed people into a false sense of security relative the “Prize” (1 Cor. 9: 24); the “just

recompense of Reward,” the “out-Resurrection,” which Paul sought to “attain” (Phil. 3:

11); the Rapture of those

found watchful and “able to escape” before the Great Tribulation will

set in, (Luke 21: 36; Rev. 3: 10), and the millennial

“inheritance” upon this earth (Rev. 20: 4; Heb. 4: 11; Rom. 8: 19-22, etc.) for

those “considered worthy of taking part in that age” (Luke 20: 35) – i.e., the Messianic Kingdom which must soon appear. This common apostasy being witnessed today, is

continually being practised by wilful neglect of conditional

promises of God: and by numerous spiritual and allegorical interpretations of responsibility

truths they seek to appease those in their congregations, who “distort the truth” by being unwilling to listen to “the whole will (‘counsel’ R.V.) of God” –

i.e., “the Gospel of God’s grace” and “about preaching the kingdom:”

(Heb. 10: 26-30; 1 Tim. 2: 12; 1 Cor. 6: 9, 10;

“Keep in mind: Blessed

experiences of the past are no

guarantees for equal fullness of blessings in the present and future. A Christ of only ‘yesterday’ does not help

you, but the living Christ of ‘to-day’ always does. Our vision must not be directed only

backwards – however fundamental our former experiences may be – but upwards and forwards. ‘It is not the beginning but the end that crowns the

Christian’s pilgrimage.” – Erich Sauer.]

Within 200 years, the English used by Wycliffe

was virtually obsolete, and a young

preacher near

To stem the tide of Bible reading and Tindale’s

alleged heresy, the bishop of

Thomas More promoted the burning of “heretics,” which ultimate led to William Tindale

being strangled and his body burned at the stake in October 1536. Sir Thomas

More, for his part, was later beheaded after running foul of the king. However, he was canonized by the Roman

Catholic Church in 1935, and in the year 2000, Pope John Paul II honoured More as the patron

saint of politicians.

Tindale received no such recognition; but, on the

other hand, his friend Miles Coverdale integrated Tindale’s translation into a

complete Bible – the first English translation from the original

languages! Every ploughboy could now

read God’s Word, and seek the Holy

Spirit’s help in its true interpretation.

The ten selected extracts from the numbered

pages of the following biography by Robert

Demaus, M. A., will give some insight into the

man whom God greatly used to change the world for good, at a time when apostate and

carnal religious leaders of the Church were seeking to withhold and distort

Divine truths from multitudes of God’s redeemed people.

Next to the study of the Bible itself, Christians

today need to study the writings and the lives of those faithful servants of God

who emphasised the need of running the “Race,” according

to the rules, in order to win the “Prize:” (1 Cor. 9: 24; Heb. 12: 1.)

W.H.T.

* *

* * *

* *

“I hold of the

souls that are departed as much as may be proved by manifest and open

Scripture, and think the souls departed in the faith of Christ and love of the

law of God, to be in no worse case than the soul of Christ was from the time

that He delivered His Spirit into the hands of His Father until the

resurrection of His body in glory and immortality.”

-

Tindale’s Rejoinder to Joye.

“I call God to recorde

against the day we shall appear before our Lord Jesus, to geue

a reckenyng of our doynges,

that I neuer

altered one syllable of God’s Word against my conscience, nor would this day,

if all that is in the earth, whether it be pleasure, honour, riches, might be geuen me.”

– Tindale’s Letter To Frith.

“I perceived by experience how that it was impossible to establish the lay

people in any truth, except the

Scripture were plainly laid before their eyes in their mother-tongue, that

they might see the process, order, and meaning

of the text.”

-

Tindale’s Preface to the Pentateuch, 1530.

“If God spare my life, ere many years I will cause a boy that driveth

the plough shall know more of the Scripture than thou doest”

- Foxe,

edition of 1563.

“Beware

of allegories; for there is not a

more handsome or apt thing to beguile withal than an allegory; nor a more

subtle and pestilent thing in the world to persuade a false matter, than an

allegory.”

- pp.287.

* *

* * *

* *

[In William Tindale’s day],

“The study of the Holy Scripture did not even form a

part of the preparatory education of those who were destined to be the

religious teachers of the people; theological

summaries, compiled by scholastic doctors took the place of the Word of God; and St.

Paul was cast into the shade by their ‘doctor sanctus,’

the ‘angel of the schools,’ ‘divus Thomas de Aquino.’ As an inevitable result, religion had

degenerated into an unprofitable round of superstitious customs and ceremonial

observances.” (pp.32.)

“In the Universities

they have ordained that no man shall look at the Scripture until he be noselled [nursed or trained] on heathen learning eight or nine years, and armed with

false principles, with which he is clean

shut out of the understanding of the Scripture.

And at his first coming unto University, he is sworn that he shall not

defame the University, whatsoever he seeth.

And when he taketh first degree,

he is sworn that he shall hold none opinions condemned by the Church; but with

such opinions be, that he shall not know.

And then, when they be admitted to study divinity, because the Scripture is locked up with such false expositions, and

with false principles of natural philosophy, that they cannot enter in, they go

about the outside, and dispute all their lives about words and vain opinions,

pertaining as much unto the healing of a man’s heel, as health of his soul:

provided yet always, lest God give His singular grace unto any person, that

none may preach except he be admitted of the Bishops.”* (pp. 45, 46.)

[* “Practice of Prelates: Works, vol. ii. P. 291.]

It was under the influence of these reflections

- (i.e., that the Holy Scriptures, and the

meaning of the passages which occurred in the services of the Church should be obscured by whimsical,

allegorical interpretations) – that

Tyndale: “perceived by experience how that it was impossible

to establish the lay people in any such truth, except the Scripture were

plainly laid before their eyes in their mother-tongue, that they might see the

process, order, and meaning of the text; for else, whatsoever truth is taught

them, these enemies of all truth quench

it again … [by] juggling with the

text, expounding it in such a sense as it is impossible to gather of the text,

if thou see the process, order, and meaning thereof.” (pp. 84.)

* *

* * *

* *

1. TINDALE’S

ATTACK ON ALLEGORICAL INTERPRETATION

The most noteworthy feature in them [the five books of Moses] is

the admirable good sense with which he insists upon the necessity of adhering

to the literal meaning of Scripture, and eschewing all manner of allegorical

interpretations. This was the

characteristic of his prefaces which would make the deepest impression upon his

contemporaries; for all true interpretations of Scripture had been lost, and

the expositor perplexed his readers with whimsical allegorical conundrums. No greater service, therefore, could be

rendered to sound theology than by thus recalling men to the only true system

of exposition; and independently, therefore, of his pre-eminent merits as a translator,

Tindale is entitled to be reverenced by all Englishmen, as the founder of all

rational Scriptural interpretation in

[* The whole Preface is well worth reading: I do

not know any better exposition of the true meaning and purpose of the

ceremonies of the Jewish economy.]

“Because that few know

and use the Old Testament, and the most part think it nothing necessary but to

make allegories, which they feign every man after his own brain at all wild

adventure, without any certain rule; therefore, though I have spoken of them in

another place [in The Obedience], yet, lest the book come not to all men’s hands that shall

read this, I will speak of them here also a word or twain.

“We had need to take

heed everywhere that we be not beguiled with false allegories, whether they be

drawn out of the New Testament or the Old, either out of any other story, or of

the creatures of the world, but namely [especially] in this book [the

Pentateuch].

Here a man had need to put on all his spectacles, and to arm himself

against invisible spirits.

“First, allegories

prove nothing; and by allegories understand examples or similitudes borrowed of

strange matters, and of another thing than that thou entreatest of. As, though circumcision be

a figure of baptism, yet thou canst not prove baptism by circumcision. For this argument were very

feeble, The Israelites were circumcised, therefore we must be baptized. And in like manner, though the offering of

Isaac were a figure or ensample of the resurrection, yet is this argument

naught, Abraham would have offered Isaac, but God delivered him from death; therefore

we shall rise again: and so forth in all other.

“But the very use of

allegories is to declare [illustrate] and open

a text, that it may be the better perceived and understood. As, when I have a clear text of Christ and

the apostles, that I must be baptized, then I may borrow an example of

circumcision to express the nature, power, and fruit, or effect of

baptism. For as circumcision was unto

them a common badge, signifying that they were all soldiers of God, to war His

war, and separating them from all other nations disobedient unto God; even so

baptism is our common badge, and sure earnest, and perpetual memorial, that we

pertain unto Christ, and are separated from all that are not Christ’s. And as circumcision was a token certifying

them that they were received unto the favour of God, and their sins forgiven

them; even so baptism certifieth us that we were washed in the blood of Christ,

and received to favour for His sake: and as circumcision signified unto them

the cutting away of their own lusts, and slaying of their free-will, as they

call it, to follow the will of God; even so baptism signifieth unto us

repentance, and the mortifying of our unruly members and body of sin, to walk

in a new life, and so forth.

“And likewise, though

that the saving of Noe, and of them that were with

him in the ship, through water, is a figure, that is to say, an example and

likeness of baptism, as Peter maketh it (1

Pet. 3), yet I cannot prove baptism therewith,

save describe it only. For as the ship

saved them in the water through faith, in that they believed God, and as the

other that would not believe Noe perished; even so

baptism saveth us through the word of faith which it preacheth, when all the

world of the unbelieving perish. And

Paul (1 Cor. 10) maketh the sea and the cloud a figure of baptism; by

which, and a thousand more, I might declare it, but not prove it. Paul also in the said place maketh the rock,

out of which Moses brought water unto the children of Israel, a figure or

ensample of Christ; not to prove Christ only; even as Christ Himself (John 3) borroweth a

similitude or figure of the brazen serpent, to lead Nicodemus from his earthly

imagination into the spiritual understanding of Christ, saying: ‘As Moses lifted up a serpent in the wilderness, so must the

Son of man be lifted up, that none that believe in Him perish, but have

everlasting life.’ By which similitude the virtue of Christ’s

death is better described than thou couldst declare it with a thousand

words. For as those murmurers against

God, as soon as they repented, were healed of their deadly wounds, through

looking on the brazen serpent only, without medicine or any other help, yea,

and without any other reason but that God hath said it should be so; and not to murmur again, but to leave their

murmuring: even so all that repent, and believe in Christ, are saved from

everlasting death, of pure grace, without, and before, their good works; and

not to sin again, but to fight against sin, and henceforth to sin no more.

“Even so with the

ceremonies of this book thou canst prove nothing, save describe and declare

only the putting away of our sins through the death of Christ. For Christ is Aaron,

and Aaron’s sons, and all that offer the sacrifice to purge sin. And Christ is all manner offering that is

offered: He is the ox, the sheep, the goat, the kid, and the lamb; He is the

goat that carried all the sin of the people away into the wilderness: for as

they purged the people from their worldly uncleannesses through blood of the

sacrifices, even so doth Christ purge us from the uncleannesses of everlasting

death with His own blood; and as their worldly sins could no otherwise be

purged, than by blood of sacrifices, even so can our sins be no otherwise

forgiven than through the blood of Christ.

All the deeds in the world, save the blood of Christ, can purchase no

forgiveness of sins; for our deeds do not help our neighbour, and mortify the

flesh, and help that we sin no more: but and if we have sinned, it must be

freely forgiven through the blood of Christ, or remain for ever.

“And in like manner of

the lepers thou canst prove nothing: thou canst never conjure out confession

thence, howbeit thou hast an handsome example there to open the binding and

loosing of our priests with the key of God’s Word; for as they made no man a

leper, even so ours have no power to command any man to be in sin, or to go to

purgatory or hell. And therefore

(inasmuch as and loosing is one power), as those priests healed no man; even so

ours cannot of their invisible and dumb power drive any man’s sins away, or

deliver him from hell or feigned purgatory.

Howbeit if they preached God’s Word purely, which is the authority that

Christ gave them, then they should bind and loose, kill and make alive again,

make unclean and clean again, and send to hell and fetch thence again; so

mighty is God’s Word. For if they

preached the law of God binding, they should bind the consciences of sinners

with the bonds of the pains of Hell, and bring them unto repentance: and then

if they preached unto them the mercy that is in Christ, they should loose them

and quiet their raging consciences, and certify them of the favour of God, and

that their sins be forgiven.

“Finally, beware of

allegories; for there is not a more handsome or apt thing to beguile withal

than an allegory; nor a more subtle and pestilent thing in the world to

persuade a false matter, than an allegory.

And contrariwise; there is not a better, vehementer or mightier thing to

make a man understand withal, than an allegory.

For allegories make a man quick-witted, and print [imprint] wisdom in

him, and make it to abide, where bare words go but in at one ear, and out at

the other. As this, with such like

sayings: ‘Put salt to all your sacrifices,’ instead of this sentence, ‘Do all your deeds with discretion,’

greeteth and biteth (if it be understood) more than plain words. And when I say, instead of these words, ‘Boast not yourself of your good deeds,’ ‘Eat not the blood not the

fat of your sacrifice’; there is a great

difference between them as there is distance between heaven and earth. For the life and beauty of all good deeds is

of God, and we are but the carrion-lean; we are only the instrument whereby God

worketh only, but the power is His: as God created Paul anew, poured His wisdom

into him, gave him might, and promised him that His grace should never fail

him, &c., and all without deservings, except that murdering the saints, and

making them curse and rail on Christ, be meritorious. Now, as it is death

to eat the blood or fat of any sacrifice, is it not (think ye) damnable to rob

God of His honour, and to glorify myself with His honour?”

Those best acquainted with the theology of the

English Reformation will be the first to admit that we shall look in vain in Cranmer, Latimer, or Ridley for any such clearness of apprehension and precision of

language as are here displayed by Tindale.

Sometimes, indeed, his language is not only precise but exquisitely

beautiful, and worthy of that master of English eloquence to whom we owe our

New Testament. Would not the reader, for

example, be inclined to believe that the following sentence from Tindale’s Preface to Exodus was

one of the gems of Jeremy Taylor? “The ceremonies were not permitted only, but also commanded

by God; to lead the people in the shadows of Moses and night of the Old

Testament; until the light of Christ and day of the New Testament were

come.”

The New Testament had been issued with an

Epistle desiring the “learned to amend it aught were

found amiss”: but those who had condemned the work as full of errors had taken no steps to provide the only

proper remedy – a translation free from errors. The prelates, “those

stubborn Nimrods which so mightily fight against God,” instead of

amending whatever needed correction, had, as Tindale indignantly protests,

stirred up the civil authorities “to torment such as tell the truth, and to burn the

Word of their soul’s health, and slay whatsoever believe thereon.” In spite of their fierce declamations,

however, he declined to be provoked into any dogmatic assertion of his own

immunity from error in that work to which he had devoted his own best industry

and learning. He had done his best; but

if he had erred through lack of knowledge he was willing to be guided by those

whose scholarship was greater than his own.

He was willing that himself, and even his work, should perish, if by any

other means the cause of God could be more successfully promoted. “I submit this book,”

such is the conclusion of his General Preface, “and

all other that I have either made or translated, or shall in time to come, if

it be God’s will that I shall further labour in His harvest, unto all them that

submit themselves unto the Word of God, to be corrected of them; yea, and

moreover to be disallowed and also burnt, if it seem worthy, when they have

examined it with the Hebrew, so [provided] that they first put forth their own

translating another that is more correct.” (pp. 282-289

* *

* * *

* *

Tindale fled to the city of

To stem the tide of Bible reading and Tindale’s

alleged heresy, the bishop of

Tyndale had not sought a controversy with this

champion of the Church; but Sir Thomas More’s book

left him no alternative. He had been

singled out by name on the very title-page of The Dialogue and had been

virtually challenged to the combat; and he had no choice except to take up the

gauntlet thus thrown down, or to acknowledge by his silence that he was unable

to defend the position which the Reformers in

Tindale with a single stroke cuts all the

intricacies of this Gordian knot; he appeals to every man, in the use of that

judgment which God hath given him, to

decide whether fact and experience confirmed what theory and assumption boasted

of demonstrating.

Whatever was gained in the controversy was

gained by Tindale. As the translator of

the New Testament, the author of The Mammon and The Obedience, he already

exercised a considerable influence over public opinion in

* *

* * *

* *

2.

CONTROVERSY WITH SIR THOMAS MORE

More’s chief resentment was

directed against Tindale’s New Testament; he declares that it was “corrupted and changed from the good and wholesome doctrine

of Christ to devilish heresies of his own,” it was “clean contrary to the Gospel of Christ”; “above a thousand texts in it were wrong and falsely

translated”; it was incurably bad and could only be amended by

translating it all afresh, for, as he wittingly remarked, “it is as easy to weave a new web of cloth as to sow up every

hole in a net*.” When pressed by quod he to give a more specific answer, Sir

Thomas adduces as unpardonable heresies the substitution of congregation

for church,

seniors

for priests, love for charity, favour

for grace,

knowledge

for confession,

repentance

for penance,

troubled

for contrite; in fact, he alleged that Tindale had, in general,

neglected the use of those words which long custom had sanctioned as being

appropriately ecclesiastical, and had adopted others which had no peculiar

association with theology.

[* Dialogue, B. iii. C. viii]

To this charge Tindale’s answer was easy and

obvious; not only was he rendering in accordance with the strict signification

of the original, but the terms which he

had avoided were depraved by so many abuses that their use could only mislead

the unwary reader. The Church

had come to be synonymous with the clergy, “the

multitude of shaven, shorn, and oiled”; the priests had almost been

confounded with the old heathen priests, their real origin and their real

purpose having almost dropped out of sight; charity had ceased to be

the name of an inward, Divine grace, and denoted the only certain outward

ostentatious deeds sanctioned by the ecclesiastics; confession, penance,

grace,

contrition

were “the great juggling words wherewith, as St. Peter

prophesied, the clergy made merchandise

of the people.” In such circumstances, to continue to

employ terms which could only convey erroneous ideas to the mind of the

ignorant reader, would be to perpetuate error, which had sprung up in defiance

of ignorance of Scripture. All such

technical language, therefore, Tindale avoided, and employed instead plain

words which had not yet been introduced into the nomenclature of the Church,

and were free from any misleading ecclesiastical associations*. The subsequent revisions of the English Bible

have not in all cases followed Tindale’s views; but circumstances have altered

since his time, and there is no longer any serious apprehension of

countenancing error or superstition by the use of terms which have been so long

isolated from their former associations.

And yet it may be doubted whether even among ourselves the proper

conception of the noblest of Christian graces has not been materially lowered

and injured by styling it charity, as Sir Thomas More

recommended, and not love, as our translator originally

rendered it.

[* Sir Thomas More justly objected to seniors,

that it only called up incongruous French associations; Tindale admits his

objection, and had already, he says, substituted it fot

the genuine English elders. (pp.319-320.)] …

Tindale does not, like More, make any systematic

attempt at employing wit an auxiliary to his argument; but he had a shrewd

humour of his own, and when he does condescend to play the satire, his retorts

are occasionally very happy. Thus, in

criticizing Sir Thomas’s elaborate distinctions concerning the amount of

reverence implied in doulia, hyperdoulia,

and latria,

he asks with exquisite irony, to which of these varieties of reverence should

be referred “the worship done by More and others to my

lord the cardinal’s hat”; alluding, of course, to the ridiculous scene

which he has described in his Practice of Prelates. He shows considerable wit also in the manner

in which he twists More, a man who “was bigamus and past the grace of his neck-verse,”

with coming forward in the strange character of the champion of the celibacy of

the clergy.

There is nothing finer in More’s

Dialogue

than the ironical comments of Tindale

upon Sir Thomas’s fundamental position, that the Church could not err in its

judgments; “whatsoever, therefore, the Church,

that is to wit, the pope and his brood say, it is God’s Word; though it be not

written, nor confirmed with miracle, nor yet good living; yea, and though they

say to-day this, and to-morrow the contrary, all is good enough and God’s Word;

yea, and though one pope condemn another, nine or ten popes a-row with all

their works for heretics, as it is to see in the stories, yet all is right and

none error. And thus good night and good

rest! Christ is brought asleep, and laid

in His grave, and the door sealed to, and the men of arms about the grave to

keep Him down with pole-axes. For that

is the surest argument to help that need, and to be rid of these babbling

heretics, that no bark at the holy spirituality with Scripture, being thereto [besides] wretches of no reputation, neither cardinals nor bishops,

nor yet great beneficed men; yea, and without totquots

and pluralities, having no hold but the very Scripture, whereunto they cleave as

burs, so fast that they cannot be pulled away, save with very singeing of them

off!*”

[* Tindale’s Answer to

More, p. 102.]

His answer to Sir Thomas’s violent peroration is

equally cogent in its argument and its sarcasm.

“Look on Tyndale,” said More, “how in his wicked book of Mammonis,

and after in his malicious book of Obedience, he showed himself so

puffed up with the poison of pride, malice, and envy that it is more than

marvel that the skin can hold together. … He barketh

against the Sacraments much more than Luther. … He knoweth that all the fathers teach

that there is a fire of purgatory, which I marvel why he feareth

so little, but if he be at a plain point with himself to go straight to hell*.”[* More’s Dialogue, p. 283; edition of 1557.] To this most bitter passage in the Dialogue,

Tindale replies with calm sarcasm: “He intendeth to purge here unto the uttermost of his power;

and hopeth that death will end and finish his

purgation. And if there be any other

purging, he will commit it to God, and take it as he findeth it, when he cometh

at it; and in the meantime take no thought thereof, but for this that is

present, wherewith all saints were purged, and were taught so to be. And Tyndale marvelleth

what secret pills they take to purge themselves, which not only will not purge here with the cross of Christ, but also

buy out their purgatory there of the pope, for a groat

or a sixpence*.”

[* Tindale’s Answer to

More, p. 214.]

If More’s Dialogue

left Tindale no choice but to attempt a reply or acknowledge himself

vanquished, Tindale’s Answer placed More

precisely in the same predicament.

Tindale had shown himself not unworthy to enter the arena with the

greatest genius in England; he had defended with unquestionable ability the

opinions of the Reformers; he had restated with the most cogent clearness the

objections which More had evaded in his Dialogue; he had roughly and

effectually silenced many of the arguments of his antagonist; and, beyond a doubt,

he remained in several points of importance master of the field. (pp.326-328.) …

The chancel wall of Old Chelsea Church is still

adorned with the handsome marble monument which Sir Thomas More had, in his

lifetime, erected for himself; over it, as if in triumphant superiority, there

was placed about 1820, by some churchwarden ignorant probably of all this

history, the memorial tablet of one of the Tindale family. Could the most ingenious sculptor have

devised a plainer or more significant allegorical record of the controversy?

(pp. 334.)

* *

* * *

* *

3.

TINDALE’S EXPOSITION OF 1 JOHN

The exposition of

In a single sentence, he lays down with

admirable succinctness the whole scope and purport of the Reformation which he

advocated: “We

restore the Scripture unto her right understanding [meaning] from your glosses, and we deliver the

sacraments and ceremonies unto their right use from your abuse.”

Sir Thomas More did not, of course, omit, in his

Confutation,

to censure Tindale’s Exposition, which he declares to have been “in such wise expounded that I dare say that blessed apostle

[John], rather than his holy words were in such a

sense believed of all Christian people, had lever [rather] his epistle had never been put in writing.” And Tindale had, in truth, given fresh

provocation to his old adversary by repeating once more, in the most offensive

manner, the imputation against his honesty, which he had already advanced in

his Answer. “Love not the world.”

The apostle said, “nor the things that are in the

world: if a man love the world, the love of the Father is not in him”;

Tindale, in his Exposition, thus comments upon these words of

“The love of the world quencheth

the love of God; Balaam, for the love of the world, closed his eyes at the

clear light which he well saw. For love

of the world the old Pharisees blasphemed the Holy Ghost, and persecuteth the

manifest truth, which they could not improve [disprove]. For love of the world many are this day

fallen away; and many which stood on the truth’s side, and defended it

awhile, for love of the world have

gotten them unto the contrary part, and are become the Antichrist of Rome’s Mamelukes, and are waxen the most wicked enemies unto the

truth and most cruel against it. They know the truth, but they love the

world: and when they espied that the truth could not stand with the honours

which they sought in the world, they hated it deadly, and both wittingly and willingly

persecuted it, sinning against the Holy Ghost: which sin shall not escape here

just unpunished; as it shall not be without damnation in the world to come; but

shall have an end here with confusion and shame, as had Judas Iscariot, the

traitor.

“And if pride,

covetousness, and lechery be the world, as St. John saith, ‘all that is in the world, as the lust of the flesh, the lust

of the eyes, and the pride of good, are not of the Father, but of the world,’ then turn your eyes unto the spirituality, unto the Roman

bishop, cardinals, bishops, abbots, and all other prelates, and see whether

such dignities be not of the world, and not whether the way to them be not also

of the world! To get the old abbot’s

treasure, I think it be the readiest way to be the new. How few come by promotion except they buy it,

or serve long for it, or both? To lusts,

and to be a good ambassador, is the only way to a bishopric; or to pay truly

for it. See whether pluralities, unions [holding

of many benefices], tot quots,

and changing the less benefice and bishopric for the greater (for the contrary

change, I trow, was never seen), may be without

covetousness and pride. And then, if

such things be the world, and the world not of God, how is our spirituality of

God? If pride be

seeking glory, and they that seek glory cannot believe, how can our

spirituality believe in Christ? If

covetousness turn men from the faith, how are our

spirituality in the faith? If Christ,

when the devil proffered Him the kingdoms of the world and the glory thereof,

refused them, as things impossible to stand with His kingdom, which is not of

the world; of whom are our spirituality, which have received them? If covetousness be a traitor, and taught

Judas to sell his Master, how should he not in so long time teach our

spirituality the same craft? … The rich persecute the true believers. The rich will never stand forth openly for

the Word of God. If of ten thousand

spring one Nicodemus, it is a great thing.”

All the other topics which Tindale had so often

treated in his former works are again introduced, and discussed, if not with

any fresh arguments, at least with unabated earnestness. A single specimen will show that his hand had

lost none of its cunning:-

“To speak of

worshipping the saints, and praying unto them, and of that we make them our

advocates well nigh above Christ, or altogether [above Christ], though it require a long disputation, yet it is as bright

as the day to all that know the truth; how that our fasting of their evens, and

keeping their holy days, going bare-foot, sticking up of candles in the bright

day, in the worshipping of them, to obtain their favour, our giving them so

costly jewels, offering into their boxes, clothing their images, shoeing them

with silver shoes with an ouch of crystal in the midst, to stroke the lips and

eyes of the ignorant, as a man would stroke young children’s heads to entice

them in, and rock them asleep in ignorance, are, with all like service, plain

idolatry, that is, in English, image-service. … And this is it that Paul calleth servire elementis mundi [to serve the elements of the world], to be in captivity under dumb ceremonies and vain

traditions of men’s doctrine, and to do the work for the work itself; as though

God delighted therein, for the deed itself, without all other respect [without

regard to anything else].

“But and [if] ye will know the true worshipping of saints, hearken unto

Paul, where he saith, ‘Ye shine as lights in the world, holding fast the word of life

unto my glory (or worship), against the day of Jesus Christ, that I have not

run nor laboured in vain.’ That is to wete,

the worship which all true saints now seek, and the worship that all the true

messengers of God seek this day, or ever shall seek, is to draw all to Christ with

preaching the true Word of God, and with the ensample of pure living fashioned

thereafter. Will ye therefore worship

saints truly? Then as what they

preached, and believe their doctrine; and as they followed that doctrine, so

conform your living like unto theirs; and that shall be unto their high worship

in the coming again of Christ (when all men’s deeds shall appear, and every man

shall be judged, and receive his reward, according to his deeds), how that they

not only, while they here lived, but also after their death, with the ensample

of that doctrine and living, left behind in writing and other memorials, [served?] unto the ensample of them that should follow them unto

Christ, that were born five hundred, yea, a thousand years after their death. This was their worship in the spirit at the

beginning … that we followed their ensamples in our deeds; as Christ

saith, ‘Let your light so shine before men that

they may see your good works, and glorify your Father that is in heaven.’ For preaching of the

doctrine, which is the light, hath but small effect to move the heart, if the

ensample of living do disagree.

“And that we worship

saints for fear, lest they should be displeased and angry with us, and plague

us or hurt us (as who is not afraid of St. Laurence? who

dare deny St. Anthony a fleece of wool, for fear of his terrible fire, or lest

he send the pox among our sheep?), is heathen image-service, and clean against

the first commandment, which is, ‘

* *

* * *

* *

3. JOYE’S

ATTACK ON TINDALE

The great work of the year in 1534, however, was

the entire revision of his New Testament, and the issue of a second edition,

which has been, not inappropriately, styled “Tindale’s

noblest monument.” Since the

first printing of the work at

The history of the English Bible between the

years 1526 and 1534 is still so badly ascertained that it cannot be given in

detail; but on the whole we may accept, as probably coming near to the truth,

the abstract given by one who has already been several times mentioned, and who

will occupy a promised place in this chapter – George Joye.

“Thou shalt know that

Tindale, about eight or nine years ago [Joye

is writing in December, 1534, of January, 1535],

translated and printed the New Testament in a mean great volume [he

means the octavo at

[* Joye, who left England in December, 1527, had

remained at Strasburg till about 1532, and therefore could only know some of

those facts from hearsay; it seems strange, however, that he had never heard of

the Colongne quarto, which had Concordances.

**Joye,

Apology, Arber’s Reprint, pp. 20-22]

In short, Joye, at the urgent request of the

printer, who was the widow of Christopher of Endhoven,

undertook to correct the press for the extremely moderate remuneration of fourpence-halfpenny sterling for every sheet of sixteen

leaves. It is probable, it is in fact

certain, that Joye omitted, through ignorance, some of the early surreptitious

reprints of Tindale’s New Testament; but from his statement it is evident that

besides Tindale’s own editions, four others had been issued previous to that

which Tindale himself revised in November, 1534. Unfortunately, these surreptitious editions

have not been identified*; but we are probably not exaggerating when we suppose

that on the average, every year since its first issue, a new edition had been

printed and circulated in England. And

it must be remembered that these editions were all reprints of the octavo of

[* They are scattered about, if they exist at

all, in cathedral libraries and other collections not easy of access. In such places, books of this kind are

practically lost (some of them have in fact disappeared); and it is a great

pity that they are not placed under proper charge in some accessible position]

Some writers, anxious to find excuses for the

authorities who prohibited the Bible and punished those that read it, allege

that it contained offensive notes, which no authority, lay or clerical, could

be expected to tolerate; but this is a total delusion, a defence of ancient

bigotry by modern ignorance. It must not

be forgotten, that what was prohibited, what was condemned, what was burnt, was

the simple text of Holy Scripture, without any note, or comment, or prologue of

any kind whatsoever.* The Bible-burners

of the sixteenth century would have repudiated with indignation the motives

which candid moderns have been kind enough to invent for them. In their judgment the whole question was

entirely free from those complications which modern refinement has introduced;

and they pronounce their opinion with a plainness which at once supersedes all

doubt.

[* I except, of course,

the edition of 1530, in which it is supposed that the Prologue to the Romans

was inserted.]

“The New Testament

translated into the vulgar tongue,” says one of the chief opponents of

the Reformers, “is in truth the food of death, the

fuel of sin, the vial of malice, the pretext of false liberty, the protection of

disobedience, the corruption of discipline, the depravity of morals, the

termination of concord, the death of honesty, the well-spring of vices, the

disease of virtues, the instigation of rebellion, the milk of pride, the

nourishment of contempt, the death of peace, the destruction of charity, the

enemy of unity, the murderer of truth!”

The men who cherished such sentiments as these should proscribe and burn

the Bible in the native tongue, was as natural as that men who dread contagion

should burn all infected garments.

The narrative of Joye, which we have just

quoted, was intended as a sort of explanation and defence of his conduct in

issuing a revised reprint of Tindale’s New Testament, although he was well

aware that Tindale himself had for some time been occupied in a careful

revision and correction of his own work.

Joye, indeed, took care not to connect Tindale’s name with his edition;

but it was undeniably little more than a reprint of Tindale’s, with a few changes

introduced. These, moreover, were made

without any attempt to confer the translation with the original Greek, a task

for which Joye’s scholarship was wholly inadequate. He himself acknowledges that he merely “mended” any words that he found falsely printed, and

that when he “came to some dark sentences that no

reason could be granted to them, whether it was by the ignorance of the first

translator or of the printers.” He had “the

Latin text” by him, and “made it plain.” In fact, the work had no pretension whatever

to be considered an original production, and was simply such a plagiarism as

any modern laws of copyright would interdict or punish. It was ushered into the world with a pompous

and affected title; “The New Testament as it was

written and caused to be written by them which heard it, whom also our Saviour

Christ Jesus commanded that they should preach it unto all creatures”;

and the colophon paraded it as “diligently over-seen

and corrected.” Not much

diligence, however, could be expected for fourpence-halfpenny

a sheet; and although the printers did their part well (for the work is got up

with remarkable neatness), Joye’s diligence seems to have been in proportion to

the smallness of his remuneration.*

[* Only one copy is known to be in existence,

that in the Grenville Library in the

The changes which he has thus introduced are few

in number, of the very smallest possible consequence, never in any case

suggested by the original Greek, and probably not in a single instance

effecting any improvement either in the accuracy or the clearness of the

version which he thus presumed to correct.

In the three chapters of St. Matthew, for example, which contain the

Sermon of the Mount, he only ventures to make eight changes: in two of them he

is certainly wrong; in a third he has mistaken the meaning of Tindale; in a

fourth he has misunderstood the sense of the original; a fifth is permissible

variation in the rendering of a participle; and the remaining three are

grammatical trifles, such as the substitution of shall for will,

into

for to. This may probably be taken as a fair specimen

of Joye’s work, which scarcely aspires beyond the province of an ordinary

corrector of the press, and, except in one respect, was, with all its

pretensions, simply a barefaced reprint of Tindale’s Testament.*

[* In St. Matthew 6:

24, Tindale’s New Testament had by mistake the words, “or else he will lene the one and

despise the other,” which Joye could make nothing of, and so,

conjecturally, he printed, “he will love the one,” etc. In Tindale’s own revision the error is of

course rectified, “he will lean to the one.” I do not pretend to have collated all Joye’s

book; but after examining several passages in the Gospels and the Epistles, I

am satisfied that the estimate in the text is a correct one. Westcott

gives an excellent account of it: History

of the English Bible, p. 57.]

One change, however, and

that not unimportant, Joye did venture with most intolerable arrogance to

introduce. In his intercourse with Tindale there had

been frequent discussions on the abstruse doctrinal question much controverted

in the Christian Church, - the condition

of the souls of the dead between death and judgment. In his controversy with Sir Thomas More,

Tindale had asserted, or, at least, had admitted, that “the souls of the dead lie and sleep till Doomsday,” whereas Joye maintained in common perhaps with

most members of the Church, Reformed or un-Reformed, that at death the souls

passed not into sleep, but into a higher and better life. On this point, according to Joye’s own

narrative, he and Tindale had frequently been engaged in rather sharp

discussions; and he complains that Tindale had repeatedly treated him in a

somewhat abrupt and un-courteous fashion, upbraiding him with his want of

scholarship, and ridiculing his arguments, “filliping

them forth,” as he alleges, “between his finger

and his thumb after his wonted disdainful manner.” Full of this doctrinal controversy, Joye

believed that Tindale had obscured the meaning of Scripture in several passages

by the use of the term resurrection, where it was

not the resurrection of the body that was really intended; and he therefore in

his revision struck out the term, and substituted for it the phrase, “life after this,” which was more in accordance with

his own opinions.

A single specimen will show more clearly than

any description the nature of the change thus effected; and the matter is of

much consequence in the personal history of Tindale, that it is necessary to

understand it accurately. The words of

our Lord (St. Matthew 22: 30, 31), rendered

in our Authorised Version, after Tindale, “in the resurrection

they neither marry nor are given in marriage … as touching the resurrection of the dead,

have ye not read?” &c., are translated by Joye, “in the life after this they neither marry” – and “as touching the life

of them that be dead,” &c.

Joye did not, as has been sometimes said, discard the word resurrection

altogether, neither did he intend to express any doubt as to the doctrine of

the resurrection of the body; but he confined the use of the word to those

instances in which it was unquestionably the resurrection of the body that was

intended (e. g. Acts 1: 22); and in all

other cases, in order, as he supposed, to avoid instilling prejudices into the

minds of the unweary readers, he employed such circumlocutions as “the life after this” or “the

very life.”

The doctrinal controversy thus raised does not

fall within the province of our biography; but some knowledge of the facts

involved is indispensable at this period of Tindale’s life, all the more so, as

they have been very considerably misrepresented by some previous writers*.

[* I am no admirer of Joye, but I cannot help

protesting against the treatment he has received from

From what has just been written the reader will

be prepared to anticipate the indignation which Joye’s proceedings excited the

mind of Tindale. For many months he had

engaged in a most elaborate revision of his New Testament, which must have cost

nearly as much labour as the original translation; and how, just as his work

was ready for the press, Joye’s edition appeared. Not only was the real author of the

translation thereby treated with the loss of the fruit of his long and weary

labours; not only was he dishonestly defrauded by the employment of his own

previous toil against himself; but, to add insult to injury, he saw his

translation tampered with by Joye, so as to give countenance to what he had

often condemned as the more “curious speculation”

of a stupid and ignorant man. Beyond all

question Joye had acted dishonourably; he had injured and insulted Tindale; and

no human patience could have submitted unmoved to his proceedings.

Tindale felt keenly the injury that had been

done; he gave vent to his indignation in bitter and reproachful terms; and a

personal controversy was thus excited, which was not appeased even at the time

of his apprehension. (pp. 438-446.)

* *

* * *

* *

4.

TINDALE’S LETTER TO FRITH

Frith had been, indeed, committed to the Tower;

but it almost appeared as if the danger which threatened him might be

dissipated. For rapid changes were

taking place in

Before intelligence of Frith’s apprehension had

reached the Continent, Tindale, who may have heard in Antwerp the dangers by

which his friend was threatened, wrote him a letter of affectionate caution;

warning him especially of the necessity of guarding against committing himself

by rash and dogmatic assertions of doctrinal questions that were not of fundamental

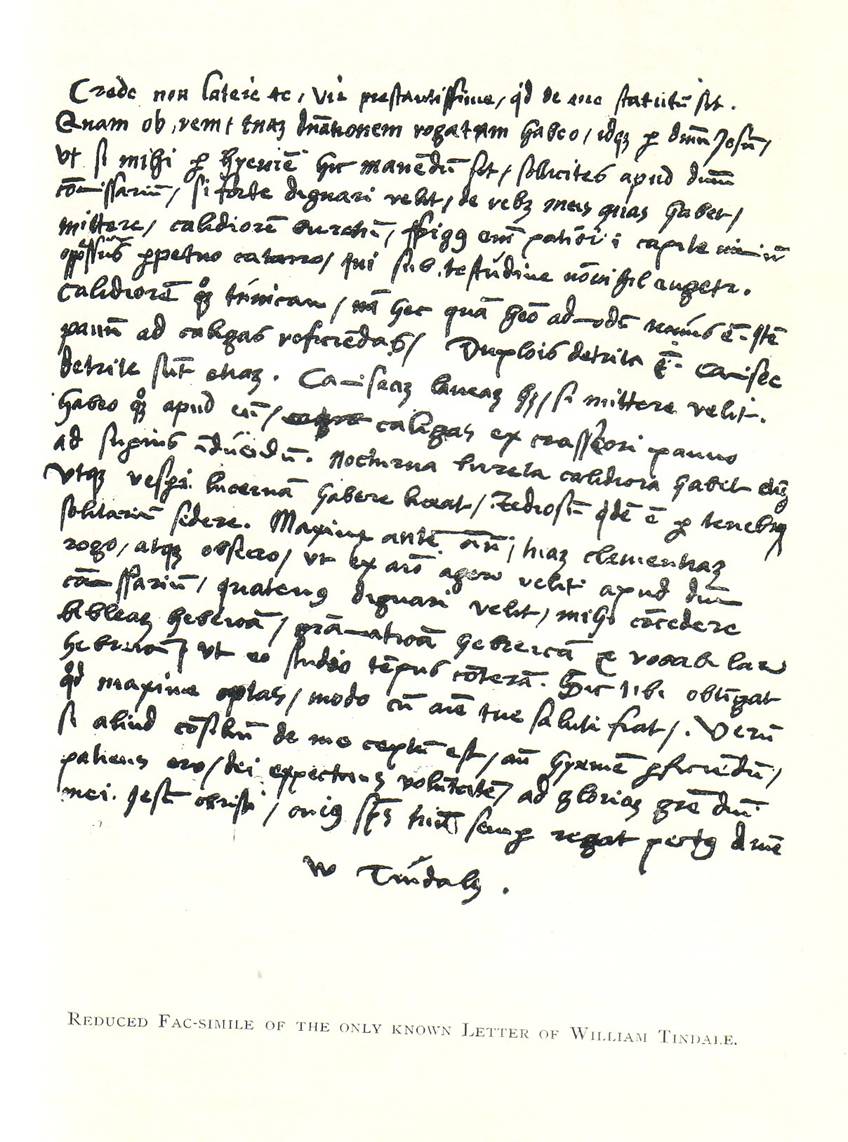

importance. Tindale’s letters,

unfortunately, have almost all perished, and the reader will, therefore, value

the more highly the few that have been preserved to us. To Frith, the dearest and most like-minded of

all his friends, he, as might have been expected, unbosoms

himself without reserve; and the letter is, accordingly, an invaluable piece of

autobiography:-

“The grace of our

Saviour Jesus, His patience, meekness, humbleness, circumspection, and wisdom, be with your heart, Amen.

“Dearly beloved brother

Jacob, mine heart’s desire in our Saviour Jesus is, that you arm yourself with

patience, and be cold, sober, wise, and circumspect: and that you keep you

a-low by the ground, avoiding high questions that pass the common capacity. But expound the law truly, and open the vail of Moses, to condemn all flesh, and prove all men

sinners, and all deeds under the law, before mercy have taken away the

condemnation thereof, to be sin and damnable: and then, as a faithful minister,

set abroach the mercy of our Lord Jesus, and let the

wounded consciences drink of the water of Him.

And then shall your preaching be with power, and not as the doctrine of

the hypocrites; and the Spirit of God shall work with you, and all consciences

shall bear record unto you, and feel that it is so. And all doctrine that casteth a mist on those

two, to shadow and hide them (I mean the law of God and mercy of Christ), that

resist you with all your power.

Sacraments without signification refuse.

If they put significations to them receive them, if you see it may help [i.e.,

may be of any spiritual advantage], though it be not

necessary.

“Of the Presence of

Christ’s body in the Sacrament, meddle as little as you can, that there appear

no division among us. Barnes [a Lutheran, and always

hot-tempered] will be hot against you. The Saxons be sore on the affirmative;

whether constant or obstinate, I remit it to God. Philip

Melanchthon is said to be with the French king [a

mistaken rumour].

There be in

“I guessed long ago,

that God would send a dazing into the head of the spiritualty, to be catched

themselves in their own subtlety; and I trust it is come to pass. And now me thinketh

I smell a Council to be taken, little for their profits in time to come. But you must understand that it is not of a

pure heart, and for love of the truth; but to avenge themselves, and to eat the

whore’s flesh, and to suck the marrow of her bones. Wherefore cleave fast to the rock of the help

of God, and commit the end of all things to Him: and if God shall call you,

that you may then use the wisdom of the worldly, as far as you perceive the

glory of God may come thereof, refuse it not: and ever among thrust in, that

the Scripture may be the mother tongue, and learning set up in the

Universities. But and if aught be

required contrary to the glory of God and His Christ, then stand fast, and

commit yourself to God; and be not overcome of man’s persuasions, which haply

shall say, we see no other way [i.e., but yielding and adjuring], to bring in the truth.

“Brother Jacob, beloved

in my heart, there liveth not in whom I have so good hope and trust, and in

whom my heart rejoiceth, and my soul comforteth herself, as in you, not the

thousand part so much of [i.e., for] your

learning and what other gifts else you have, as that you will creep a-low by

the ground, and walk in those things that the conscious may feel, and not in

the imaginations of the brain; in fear, and not in boldness; in open necessary

things, and not to pronounce of define of hid secrets, or things that neither

help or hinder, whether they be so or no; in unity, and not in seditious

opinions; insomuch that if [i.e., although] you

be sure you know, yet in things that may abide leisure, you will defer, or say

(till other agree with you), ‘Methink the text requireth this sense or understanding’;

yea, and that if [i.e., although] you be sure

that your part be good, and another hold the contrary, yet if it be a thing

that maketh no matter, you will laugh and let it pass, and refer the thing to

other men, and stick you stiffly and stubbornly in earnest and necessary

things. And I trust you be persuaded so

of me. For I call God to record against

the day we shall appear before our Lord Jesus, to give a reckoning of our

doings, that I never altered one syllable of God’s Word against my conscience,

nor would this day, if all that is in the earth, whether it be pleasure,

honour, or riches, might be given me.

Moreover, I take God to record to my conscience, that

I desire of God to myself, in this world, no more than that without which I

cannot keep His laws.

“Finally, if there were in me any gift that could help at hand, and aid you if

need required, I promise you I would not be far off, and commit the end to God:

my

soul is not faint though my body be weary. But God

hath made me evil-favoured in this world, and without grace in the sight of

men, speechless and rude, dull and slow-witted. Your part shall be to supply that lacketh in

me; remembering that as lowliness of heart shall make you high with God, even

so meekness of words shall make you sink into the hearts of men. Nature giveth grace authority; but meekness

is the glory of youth, and giveth them honour.

Abundance of love maketh me exceed in babbling.

“Sir, as concerning

purgatory, and many other things, if you be demanded, you may say, if you err,

the spirituality hath so led you; and that they have taught you to believe as

you do. For they preached you all such

things out of God’s Word, and alleged a thousand

texts; by reason of which texts you believed as they taught you. But now you find them liars, and that the

texts mean no such things, and, therefore, you can believe them no longer; but

are as ye were before they taught you, and believe no such thing; howbeit you [may

say you] are ready to believe, if they have any other way to prove it; for without proof you cannot

believe them, when you have found them with so many lies, &c. If you perceive wherein we may help, either

in being still, or doing somewhat, let us have a word, and I will do mine

uttermost.

“My Lord of London hath

a servant called John Tisen, with a red beard, and a black reddish head, and

was once my scholar; he was seen in

“The mighty God of

Jacob be with you to supplant His enemies, and give you the favour of Joseph;

and the wisdom and the spirit of Stephen be with your heart and with your

mouth, and teach your lips what they shall say, and how to answer to all

things. He is our God, if we despair in

ourselves, and trust in Him; and His is the glory. Amen.

“William Tindale.

“I hope our redemption is nigh.”

Tindale’s warning came too late. Before his letter reached

… In these circumstances

nothing remained for Frith but, if possible, to defend his opinion, and to show that what he had taught was in

accordance with the plain sense of Scripture and the writings of the early

fathers. (pp. 411-417.)

* *

* * *

* *

5. TINDALE

ON THE LORD’S SUPPER

On April 5, 1533, there appeared from the press

of “Nicholas Twonson of Nerembery,” a treatise entitled, “The Supper of the Lord. … wherein incidentally M. More’s letter

against John Frith is confuted.”

The work, indeed, was published anonymously, and was by some supposed to

be that very treatise by George Joye of which Tindale, in his letter to Frith,

had spoken in such disparaging terms.

Others, however, ascribed to book to Tindale; and Sir Thomas More, who

immediately published a refutation of it, though admitting that the work was

not characterized by the customary learning of Tindale, and branding it as “blasphemous and bedlam-rife,” yet proceeds to argue upon

the assumption that Tindale was really its author. Foxe has not

printed it with the rest of Tindale’s writings, but speaks doubtfully if it as

“a short and pithy treatise touching the Lord’s

Supper, compiled, as some do gather, by Tindale, because the method and phrase

agree with his, and the time of writing is concurrent.” On the whole, however, it seems now agreed that the work was

Tindale’s, this conviction being strengthened by the fact that Joye, whose

self-conceit was boundless, does not claim the authorship of it, as he

certainly would have done had the work been his*.

[* On the point, which is not devoid of

interest, the reader is referred to the excellent prefatory remarks of Professor Walter in Tindale’s Works,

vol. iii. pp. 218 &c., and three letters in Notes and Queries, First

Series.]

The treatise is, in reality, and exposition of

the sixth chapter of John, and is not unworthy of Tindale’s acuteness as a

controversialist; it retorts upon More with very great

logical skill; and it exposes with very

considerable force the absurdities and contradictions involved in the doctrine

of transubstantiation. To the

ordinary modern reader, however, much the most interesting and characteristic

part of the treatise is that in which Tindale sketches his ideal of the

Supper. We present it without note or

comment to the judgment of the reader:-

“This holy sacrament

therefore, would God it were restored unto the pure

use, as the apostles used it in their time!

Would God the secular princes, which should be the very pastors and head

rulers of their congregations committed unto their care, would first command or

suffer the true preachers of God’s Word to preach the Gospel purely and

plainly, with discreet liberty, and constitute over each particular parish such

curates as can and would preach the word, and that once or twice in the week,

appointing unto their flock certain days, after their discretion and zeal to

God-ward, to come together to celebrate the Lord’s Supper! At the which assembly the curate would propone and declare them, first, this text of Paul, 1 Cor. 11: ‘So oft as ye shall eat

this bread, and drink of this cup, see that ye be joyous, praise, and give

thanks, preaching the death of the Lord,’

&c. : which declared, and every one exhorted to prayer, he would preach

them purely Christ to have died and been offered upon the altar of the cross

for their redemption; which only oblation to be sufficient sacrifice, to peace

the Father’s wrath, and to purge all the sins of the world. Then to excite them with all humble

diligence, every man unto the knowledge of himself and his sins, and to believe

and trust to the forgiveness in Christ’s blood; and for this so incomparable

benefit of our redemption (which were sold bondmen to sin), to give thanks unto

God the Father for so merciful a deliverance through the death of Jesus Christ,

every one, some singing, and some saying devoutly, some or other psalm, or

prayer of thanksgiving, in the mother tongue.

Then, the bread and wine set before them, in the face of the Church,

upon the table of the Lord, purely and honestly laid, let him declare to the

people the significations of those sensible signs; what the action and deed

moveth, teacheth, and exhorteth them unto; and that the bread and wine be no

profane common signs, but holy sacraments, reverently to be considered, and

received with a deep faith and remembrance of Christ’s death, and of the

shedding of His blood for our sins; these sensible things to represent us the

very body and blood of Christ, so that while every man beholdeth with his

corporal eye those sensible sacraments, the inward eye of his faith may see,

and believe steadfastly, Christ offered and dying upon the cross for his sins,

how His body was broken and His blood shed for us, and hath given Himself whole

for us, Himself to be all ours, and whatsoever He did to save us, as to be made

for us, of His Father, our righteousness, our wisdom, holiness, redemption,

sanctification, &c.

“Then let this preacher

exhort them lovingly to draw near unto this table of the Lord, and that not

only bodily, but also, their hearts purged by faith, garnished with love and

innocency, every man to forgive each other unfeignedly, and to express, or at

leastwise to endeavour them to follow, that love which Christ did set before

our eyes at His last supper, when He offered Himself willingly to die for us

His enemies; which incomparable love to command, bring in Paul’s arguments, so

that thus this flock may come together, and be joined into one body, one

spirit, and one people. This done, let

him come down, and, accompanied honestly with other ministers, come forth

reverently unto the Lord’s table, the congregation now set round about it, and

also in their other convenient seats, the pastor exhorting them all to pray for

grace, faith, and love, which all this sacrament signifieth and putteth them in

mind of. Then let there be read apertly

and distinctly the sixth chapter of John, in their mother tongue; whereby they

may clearly understand, what it is to eat Christ’s flesh and to drink His

blood. This done, and some brief prayer

and praise sung or read, let one or other minister read the eleventh chapter of

the first [Epistle] to the Corinthians, that

the people might perceive clearly, of those words, the mystery of this Christ’s

supper, and wherefore He did institute it.

“These with such like

preparations and exhortations had, I would every man present should profess the

articles of our faith openly in our mother tongue, and confess his sins

secretly unto God; praying entirely that He would now vouchsafe to have mercy

upon him, receive his prayers, glue his heart unto Him by faith and love,

increase his faith, give him grace to forgive and to love his neighbour as

himself, to garnish his life with pureness and innocency, and to confirm him in

all goodness and virtue. Then again it

behoveth the curate to warn and exhort every man deeply to consider, and expend

[i.e. weigh] with himself, the signification

and substance of his sacrament, so that he sit not down an hypocrite and a

dissembler, since God is searcher of heart and reins, thoughts and affections,

and see that he come not to the holy table of the Lord without that faith which

he professed at his baptism, and also that love which the sacrament preacheth

and testifieth unto his heart, lest he, now found guilty of the body and blood

of the Lord (that is to wit, a dissembler with Christ’s death, and slanderous

to the congregation, the body and blood of Christ), receive his own damnation. And here let every man fall down upon his

knees, saying secretly with all devotion their Paternoster in English;

their curate, as example, kneeling down before them: which done, let him take

the bread and eft [i.e. after] the wine in the sight of the people, hearing him with a

loud voice, with godly gravity, and after a Christian religious reverence,

rehearsing distinctly the words of the Lord’s Supper in their mother tongue;

and then distribute it to the ministers, which, taking the bread with great

reverence, will divide it to the congregation, every man breaking and reaching

it forth to his next neighbour and member of the mystic body of Christ, other

ministers following with the cups, pouring forth and dealing them the wine,

altogether thus being now partakers of one bread and one cup, the thing thereby

signified and preached printed fast in their hearts. But in this meanwhile must the minister or

pastor be reading the communication that Christ had with His disciples after

His supper, beginning at the washing of

their feet; so reading till the bread and wine be eaten and drunken, and

all the action done: and then let them fall down on their knees, giving thanks

highly unto God the Father for His benefit and death of His Son, whereby now by

faith every man is assured of remission of his sins; as this blessed sacrament

had put them in mind, and preached it them in this outward action and

supper. This done, let every man commend

and give themselves whole to God, and depart*.” (pp. 419-424.)

[* Tindale’s Works, vol. iii pp. 256, &c.]

* *

* * *

* *

6.

TINDALE’S SECOND LETTER TO FRITH

Tindale, learning the fresh danger which

threatened his friend, wrote once again to comfort and strengthen

him for the terrible trial which awaited him.

It is exceedingly doubtful whether Tindale’s epistle ever reached Frith;

whether, in fact, Frith had not been martyred before it was dispatched or even

penned; but it is pervaded by the very spirit in which Frith acted, and thus

affords a most touching illustration of the perfect “like-mindedness”

by which the two friends were animated. Foxe has

entitled it, “A letter from William Tyndale, being in

“The grace and peace of

God our Father, and of Jesus Christ our Lord, be with you. Amen.

Dearly beloved brother John, I have heard say that the hypocrites, now

they have overcome that great business which letted

them [i.e., the royal divorce], or that now

they have at the least way brought it at a stay, they return to their old

nature again. The will of God be

fulfilled, and that [what] He hath ordained to

be ere the world was made, that come, and His glory reign over all.

“Dearly beloved,

howsoever the matter be, commit yourself wholly and only unto your most loving

Father and most kind Lord, and fear not

men that threat, nor trust men that speak fair: but trust Him that is true of promise, and able to make His word good. Your cause is Christ’s Gospel, a light that

must be fed with the blood of faith. The

lamp must be dressed and sniffed daily, and that oil poured in every evening

and morning, that the light go not out. Though we be sinners, yet is the cause

right. If when we be

buffeted for well-doing, we suffer patiently and endure, that is thankful with

God; for to that end we are called. For Christ also suffered for us, leaving us an example that we should

follow His steps, who did no sin.

Hereby have we perceived love, that He laid

down His life for us; therefore we ought also to lay down our lives for the

brethren. Rejoice and be glad, for great

is your reward in heaven. For we suffer

with Him, that we may also be glorified: who shall change our vile body,

that it may be fashioned like unto His glorious body, according to the working

thereby He is able even to subject all things unto Him.

“Dearly beloved, be of

good courage, and comfort your soul with

the hope of this high reward, and bear the image of Christ in your mortal

body, that it may at His coming be

made like unto His, immortal: and follow the example of all your other dear

brethren, which chose to suffer in hope

of a better resurrection. Keep your

conscience pure and undefiled, and say against that nothing. Stick at [i.e. resolutely maintain] necessary things; and remember the blasphemies of the

enemies of Christ, ‘They find none but that will adjure rather than suffer the

extremity.’ Moreover, the death of them

that come again [i.e. repent] after they have once

denied, though it be accepted with God and all that believe, yet is it not

glorious; for the hypocrites say, ‘He must needs die; denying helpeth not: but

might it have holpen, they would have denied five hundred times: but seeing it

would not help them, therefore of pure pride, and mere malice together, they

speak with their mouths that [i.e. what] their

conscience knoweth false.’ If you give yourself, cast yourself,

yield yourself, commit yourself wholly and only to your loving Father; then

shall His power be in you and make you strong, and that so strong, that you

shall feel no pain, and [in?] that shall be to

another present death: and His Spirit shall speak in you, and teach you what to

answer, according to His promise. He

shall set out His truth by you wonderfully, and work for you above all that

your heart can imagine. Yea, and you are not yet dead; though the hypocrites all,

with all they can make, have sworn your death.

Una salus vivtis nullam sperare salutem.

To look for no man’s help bringeth

the help of God to them that seem to be overcome in the eyes of the

hypocrites: yea, it shall make God to carry you through thick and thin for His

truth’s sake, in spite of all the enemies of His truth. There falleth not a hair till His hour be come: and when His hour is come, necessity carrieth us

hence, though we be not willing. But if

we be willing, then have we a reward and thanks.

“Fear not threatening,

therefore, neither be overcome of sweet words; with

which twain the hypocrites shall assail you.

Neither let the persuasions of

worldly wisdom bear rule in your heart; no, though they be your friends that

counsel. Let Bilney

be a warning to you. Let not your visor beguile your eyes.

Let not your body faint. He that endureth to the end shall be saved. If the pain be above your strength, remember,

‘Whatsoever ye shall ask in My

name, I will give it you.’ And pray to your Father in that name, and He will cease your pain, or shorten it. The Lord of peace, of hope, and of faith, be with you. Amen.

“William Tyndale.

“Two have suffered in

[* Editors have conjectured that by Riselles, Brussels is meant; and that Luke is the suburb of Brussels, now

called Laeken:

the very slightest inquiry would have informed them that Riselles

is the Flemish name of Lille,

as Luke is of Liege.]

“If, when you have read

this, you may send it toAdrian [or John Byrte], do, I pray, that he may

know that our heart is with you.

“George Joye at Candlemas, being at Barrow, printed two leaves of Genesis

in a great form, and sent one copy to the king, and another to the new Queen [Anne

Boleyn], with a letter to N. for to deliver them; and

to purchase licence, that he might so go through all the Bible. Out of that is sprung the noise of the new

Bible [report that there was to be a new translation]; and out of that is the great seeking for English books at

all printers and bookbinders in Antwerp, and for an English priest that should

print [i.e. that intended to print].

“This chanced the 9th

day of May.

“Sir, your wife is well

content with the will of God, and would not, for her sake, have the glory of

God hindered.

“William Tyndale,”

(pp. 428-432.)

* *

* * *

* *

7. TINDALE

AS A REVISER

But before entering upon the narrative of this

personal dispute, the work of Tindale deserves a more detailed notice. Tindale’s first version had been made under

considerable difficulties, as we have formerly seen; and he was himself aware

that it was susceptible of many improvements.

Not only might the text be improved by more accurate, more clear, or

more concise, renderings; but, in his own estimation, it was desirable to give

the work completeness by separate introductions to each of the books, and by

greater attention to the marginal glosses, with which, as with a brief

commentary, it was equipped. All this

was accomplished with great pains in the edition of 1534. He had diligently gone over the whole of his

translation, not only comparing it once again with the Greek text of Erasmus,

but bringing to bear upon it that enlarged experience of Hebrew which he had

acquired in his translation of the Old Testament, and which he now saw to be of

no small service in illustrating the Hellenistic of the New. In his “Epistle to

the Reader,” he states the general principles on which he proceeded, and

they are not unworthy of consideration.

“Here hast thou, most

dear reader, the New Testament or covenant made with God in Christ’s blood,

which I have looked over again, now at the last, with all diligence, and

compared it unto the Greek, and have weeded out of it many faults, which lack

of help at the beginning, and oversight, did sow therein. If aught seem changed, or not altogether

agreeing with the Greek, let the finder of the fault consider the Hebrew phrase

or manner of speech left in the Greek words; whose preterperfect

tense and present tense is often both one, and the future tense is the

operative mood also, and the future tense oft the imperative mood in the active

voice, and in the passive ever. Likewise

person for person, number for number, and an interrogation for a conditional,

and such like, is with the Hebrews a common usage*. I have also in many places set light in the

margin to understand the text by. If any

man find faults either with the translation or ought beside (which

is easier for many to do than so well to have translated it themselves of their

own pregnant wits at the beginning, without an ensample), to the same

it shall be lawful to translate it themselves, and to put what they lust

thereto. If I shall perceive, either by

myself or by my information of other, that aught be

escaped me, or might more plainly be translated, I will shortly after cause it

to be mended. Howbeit,

in many places methinketh it better to put a declaration in the margin, than to

run too far from to text. And in

many places, where the text seemeth at the first chop hard to be understood,

yet the circumstances before and after, and often reading together, make it

plain enough.”